Thousands of people in Dhaka will come out in droves to celebrate Pohela Boishakh, eating hilsha fish and panta bhaat across hundreds of restaurants. Our social media feeds will be abuzz with activity. But what will we do about the Ghosts of Boishakhs Past?

In Economics, we often talk about the invisible hands of the market, referring to the interplay of supply and demand. In sociology, perhaps we can find room for a similar terminology to refer to the interplay between the forces and life and death.

The idea that a person’s life (or death) cannot be assigned a value is redundant at best and outrageous at worst. Otherwise, society wouldn’t mourn some deaths at the cost of remaining silent over others. Similarly, some lives are clearly more valued than others. And in Bangladesh, it’s quite safe to say that female lives are valued categorically less than male lives.

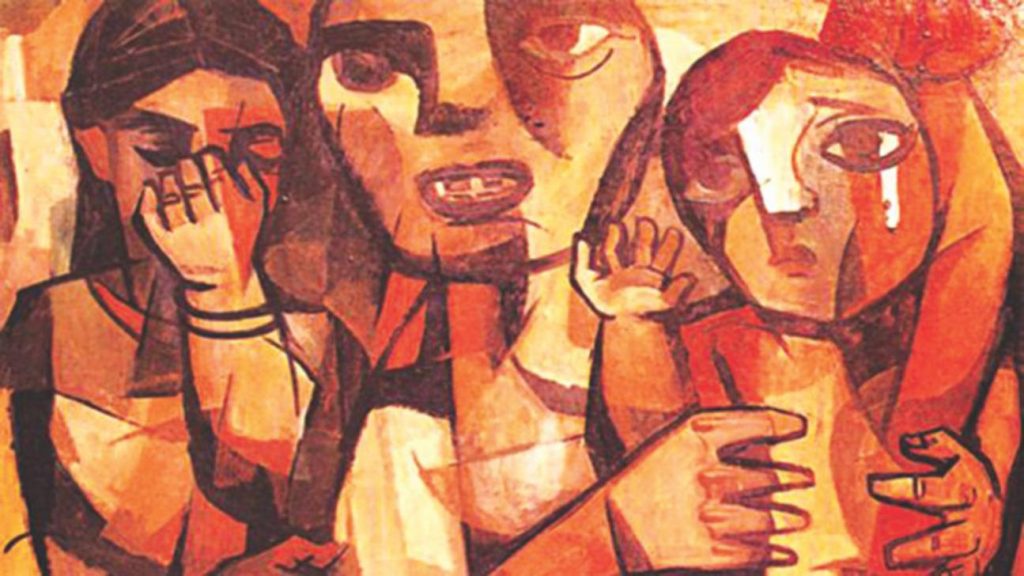

Nusrat Jahan Rafi is simply the latest victim of ths interplay between these insidious forces. Four years ago, there were others: on April 14, at least twenty women were assaulted by unknown perpetrators in broad daylight, in the heart of Dhaka University.

The initial investigation failed to identify any individual involved with the crime in, although one suspect was subsequently arrested on January 27, 2016 when the case was reopened.

The echoes of these incidents are now all too familiar to our weary populace. The names of these survivors become markers of their own. When we talk about the incident that happened around 2000, for instance, we talk about Badhon, whose clothes were ripped off on a new year’s eve. Why must we mention the victim’s name only?

When we mention the holocaust, do we mention a random Jewish survivor, or do we speak about Hitler, and his unthinkable malice, that resulted in something as dastardly as the Final Solution? Yes, rapists aren’t as bad as Hitler. But to say that an apple that’s only blackened is not as bad as a poisoned apple is missing the point.

The point is, that anyone could be Hitler. That’s a fact that even neo-fascists in Bangladesh are only too aware of. And in that vein, any man could be a rapist. That’s a reality of the world we live in.

Nations Suffer When Rape Culture Thrives

To say that rape culture is thriving in Bangladesh would be an understatement. Most of us are aware, to varying extents, of the many shapes and forms misogyny takes in our society. That’s a conversation for other days. This conversation is about us taking a more proactive role towards the women in our lives by supporting them wherever we see oppression taking root.

And it’s the roots which we must pay close attention to. During the Liberation War of 1971, some 200,000 women were systematically raped by the Pakistani Army.

“The Khans tied our hands, burned our faces and bodies with cigarettes. There were thousands of women like me,” said Aleya Begum, a Birangona. Birangona is a Bangali word that means brave woman. “They gang raped us many times a day. My body was swollen, I could barely move. They still did not leave us alone. They never fed us rice, just gave us dry bread once a day and sometimes a few vegetables. Even the Biharis, who supported the Pakistani army, tortured us. We tried to escape but always failed. When the girls were of little use they killed them.”

An article in the Dhaka Tribune talked about the legacy of 1971 in context of rape culture. “Afsan Chowdury’s purported claim that the destigmatisation of rape was “the most significant” legacy of Pakistan, that the 1971 breakdown of norms regarding public rape allowed impunity regarding rape to become the norm, is intriguing. Bangladesh, however, did not merely continue impunity for Pakistani and razakar rapists, they gave impunity for rapists from our own freedom fighters.”

After the war, most Birangonas were silenced and ostracized by their communities. Many of them moved to India to give birth; many others committed suicide after finding no refuge within their families.

“We lost everything, our reputation, children, husbands, homes, we did not want them to get away with it,” said Aleya Begum, breaking down several times while telling her story to DW.

“There was hatred in our hearts, we were determined to kill the Khans and save the country. We fought with the Himayat Bahini. But nobody remembers us. Where is our name in history? Which list? Nobody wants to thank us. Instead we got humiliation, insults, hatred, and ostracism.”

The seeds of this rape culture has sprouted, and today, nearly fifty years after independece, they have emerged as insidious, hardy trees. Their snake-like branches are present within the minds of men and women alike. Everyone knows what rape culture is like. It’s just that no one really talks about it.

The process of fighting against a dominant rape culture is a long arduous process, one that will perhaps outlast most, if not all of our lives, but the cost it incurs must be paid. Progress must not be measured not only in terms of economic growth, but also in other measures of development.

The Case for Greater Security

In the wake of the 2015 incident, the police has increased their security at Pohela Boishakh hotspots every year since then. “It is indeed a challenging task to provide security for such a large scale event,” said RAB Director General Benazir Ahmed in a press conference in 2018. “Nonetheless, ensuring safety and security of the citizens is our top priority. We are taking the necessary preparations. We will deploy troops in all major locations including Ramna Batamul and Rabindra Sarobar, where events and rallies will take place.

We will also keep close watch through CCTVs and observation posts. We are staying alert to spot any suspicious activities in nearby hotels and slums. RAB members are keeping an eye out for militant activities as well.”

In 2019, DMP Commissioner Asaduzzaman Mia said, “A special team will be deployed to counter sexual harassment, along with other extensive security measures to ensure foolproof safety at the Pohela Boishakh celebrations in Dhaka.”

Of course, we can’t police everyone else on our own to ensure the safety of women and children in crowds. The best we can do is remain vigilant that a similar incident doesn’t take place in front of our eyes. Yet, perhaps, the hard work of rehabilitating our collective unconsciousness comes after Pohela Boishakh is over, when we return to the monotony of our daily lives.

The Hard Work of Rehabilitating Our Collective Psyches

Women empowerment campaigns can only work if we allow ourselves to change, and also if we encourage that kind of change in our close circles. As things stand, the statistics tell the bitter truth. According to a 2013 study by UNDP, 82% of rural Bangladeshi and 79% of urban Bangladeshi men who had raped felt they were entitled to rape women. Furthermore, 61.2% of urban Bangladeshi men who had raped did not feel guilty or worried afterwards, and 95.1% experienced no legal consequences.

While waves of progress have washed over Bangladesh since 2013, it’s doubtful if such grim numbers have changed significantly since then. Can they be changed? That’s not the right question to ask. Otherwise, if we resign ourselves to fate, then what hope, truly, do we live for our future?

Perhaps we can mull these thoughts over when Pohela Boishakh is done. I suppose the ghosts of Boishakhs Past have bothered everyone enough for the year. These ghosts will now quietly return to their cursed cages, flickering silently while people walk through them. Such is the fate of such ghosts in Bangladesh, and perhaps of all ghosts throughout the country.