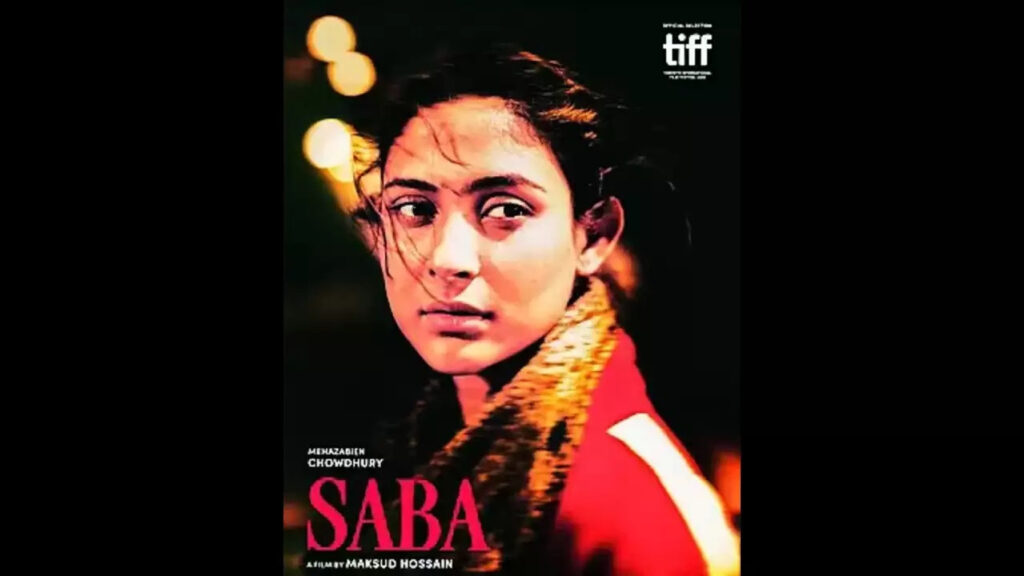

Maksud Hossain’s directorial debut Saba is more than just a movie—it’s a reflection of the economic and emotional battles that so many people in our country face. Right from the opening scenes, the film thrusts us into the world of Saba, a young woman whose life has been overtaken by the relentless demands of caregiving for her paraplegic mother. The weight of this responsibility, combined with the suffocating economic realities of Dhaka, makes Saba not just a compelling narrative, but a poignant social commentary on the frustrations and limitations that many of us experience. Saba, played with haunting subtlety byMehazabien Chowdhury, is a 24-year-old woman who has sacrificed everything for her bedridden mother, Shirin (Rokeya Prachy). Her own dreams—education, career, independence—have been put on hold indefinitely as she juggles her mother’s needs with the harsh realities of their financial situation. It’s a story that, as a Bangladeshi, resonated deeply with me. There are so many people I know—women especially—who face similar circumstances, where family responsibility takes precedence over their own desires. One of the things that stood out to me immediately was the film’s portrayal of Dhaka—not as the bustling city of opportunities it’s often painted as in popular media, but as a place of economic disparity and frustration. Saba’s home is a vibrant space, filled with colorful walls and objects, but the atmosphere inside is stifling. Her world is small, confined to the needs of her mother and the looming threat of financial ruin. I could feel the weight of those small rooms—the claustrophobia of a life that seems stuck in place. It’s a feeling that I think many Bangladeshis can relate to, especially those of us who have witnessed or experienced the gap between the country’s growing wealth and the struggles of the majority.

Saba, played with haunting subtlety byMehazabien Chowdhury, is a 24-year-old woman who has sacrificed everything for her bedridden mother, Shirin (Rokeya Prachy). Her own dreams—education, career, independence—have been put on hold indefinitely as she juggles her mother’s needs with the harsh realities of their financial situation. It’s a story that, as a Bangladeshi, resonated deeply with me. There are so many people I know—women especially—who face similar circumstances, where family responsibility takes precedence over their own desires. One of the things that stood out to me immediately was the film’s portrayal of Dhaka—not as the bustling city of opportunities it’s often painted as in popular media, but as a place of economic disparity and frustration. Saba’s home is a vibrant space, filled with colorful walls and objects, but the atmosphere inside is stifling. Her world is small, confined to the needs of her mother and the looming threat of financial ruin. I could feel the weight of those small rooms—the claustrophobia of a life that seems stuck in place. It’s a feeling that I think many Bangladeshis can relate to, especially those of us who have witnessed or experienced the gap between the country’s growing wealth and the struggles of the majority.

Saba is more than just a story of familial duty; it’s also a sharp critique of the systems that fail people like Saba. The film subtly but effectively critiques the growing wealth gap in Bangladesh. There’s a radio report that casually mentions the rise of a millionaire class, a stark contrast to the world Saba inhabits, where scraping together enough money for her mother’s surgery seems impossible. As someone who’s seen firsthand how difficult it can be for people to access even basic healthcare in Bangladesh, this hit hard. Hossain doesn’t need to spell it out for us—the film’s narrative and setting do all the talking.

Saba’s desperation leads her to take a job at a hookah lounge, a decision that feels both necessary and humiliating. The lounge, bathed in neon lights and filled with men who treat her with a mix of suspicion and condescension, represents a different kind of prison for Saba. Yet, as uncomfortable as this job is, it’s her only option, and watching her navigate this environment was heartbreaking. IIt’s a grim reminder of how gender and class intersect in ways that leave women particularly vulnerable in our society.

The relationship that develops between Saba and Ankur (Mostafa Monwar), the lounge manager, is another element of the film that I found compelling. Ankur, like Saba, is trapped in his own way—managing a shady business while secretly running an illicit alcohol trade on the side. Their bond is built on a mutual understanding of survival in a system that offers them few options. While the film hints at a potential romance, it never goes down that path fully, and I appreciated that. The connection between them isn’t romantic in the traditional sense—it’s more about the shared experience of being stuck in lives they didn’t choose.

The heart of the film, though, is Saba’s relationship with her mother, Shirin. Shirin is bitter, demanding, and often ungrateful for the sacrifices Saba makes for her. Yet, beneath her harsh exterior, there’s a vulnerability that makes it clear she’s trapped too—both by her physical condition and by the weight of her own past. Watching these two women struggle to communicate, each frustrated with the other’s inability to meet their needs, felt painfully real.

As the film progresses, Saba’s obsession with saving her mother becomes more intense, to the point where it starts to feel like an addiction. She will do anything—sacrifice anyone—to keep her mother alive, even though it’s clear that this fixation is slowly destroying her. But there is not much she can do to prevent that.

In a cultural context where caregiving is often seen as a duty, it often becomes emotionally and physically exhausting to the point that it consumes the caregiver’s entire identity. In a way, caregiving is a form of silent self-sacrifice, one that is rarely given its due appreciation, if at all.In a painfully real exhibition of it, by the end of the film, Saba loses sight of who she is outside of her role as her mother’s caretaker.

Caregiving starts off as a form of love, at least viewed by society as such. However, to expect a single person to take on that burden, discarding their own dreams and aspirations, is unfair and frustrating even when that person is your mother. But the society will condemn you and regard you as disrespectful if you ever voice out these frustrations. In that way, Hossain’s decision to portray such a sensitive topic is incredibly impactful and eye-opening.

Mehazabien Chowdhury’s performance is what makes all of this feel so real. There’s a quiet strength to her portrayal, but also a deep vulnerability. She never overplays the role—there’s no melodrama here, just the slow unraveling of a woman who’s been asked to give too much for too long. Chowdhury’s performance, combined with Hossain’s restrained direction, keeps the film from tipping into sentimentality. It’s raw, but never overly emotional. The pain feels lived-in, not performed.

The film’s pacing is another thing I appreciated. At just 95 minutes, Saba doesn’t waste time, but it also doesn’t rush. Hossain allows the tension to build gradually, letting the audience sit with Saba in her quiet moments of desperation. There are no grand, dramatic flourishes—just the slow, steady accumulation of small indignities and compromises that make up her life. The editing by Sameer Ahmed is clean and unobtrusive and allows the story to flow without unnecessary distractions.

One of the most impactful aspects of Saba was showing how even the most mundane of desires can turn into impossible dreams because of circumstances that are beyond your control. Especially in a country burdened with economic hurdles and disparity like ours, the gap between what we want and what we can have often feels insurmountable. Saba dreams of a life beyond her mother’s illness, Ankur dreams of escaping to Europe away from the complicated and dangerous world he has found himself in.

Shirin dreams of freedom—from her illness, from her daughter’s constant care. These characters’ dreams are simple and universal, but their circumstances make them feel impossible to achieve.

By the time the film reaches its conclusion, it doesn’t offer any easy answers. Saba’s journey doesn’t end with triumph or relief—it simply continues, as life often does. This might frustrate some viewers, but for me, it felt like the most honest way to tell this story. Life doesn’t always wrap up neatly, and sometimes, we’re left to carry the weight of our burdens without the promise of release. For anyone who’s lived with the pressure of family expectations, economic hardship, or the emotional toll of caregiving, Saba offers a reflection of those experiences that is both raw and tender. It’s a film that lingers long after the credits roll, reminding us that even in the most difficult circumstances, there is strength in simply enduring.