White supremacist attacks do not happen in a vacuum. According to the New York Times, at least a third of white extremist attacker’s since 2011 were inspired by other white supremacist killers, often expressing admiration for them and their tactics.

The Christchurch shooter, for instance, was cited as an inspiration by both the Poway synagogue shooter and the El Paso shooter. There are online forums, such as 8chan, where these attacks are not only documented, but celebrated. Anders Brevik, who killed 77 in a mass shooting incident in Norway in 2011, is often revered by many in these forums, most notably by the Christchurch attacker.

“I think that Breivik was a turning point, because he was sort of a proof of concept as to how much an individual actor could accomplish,” said J.M. Berger, an author researching terrorism.

These attackers often leave behind manifestos or statements indicating the reasons behind their actions.

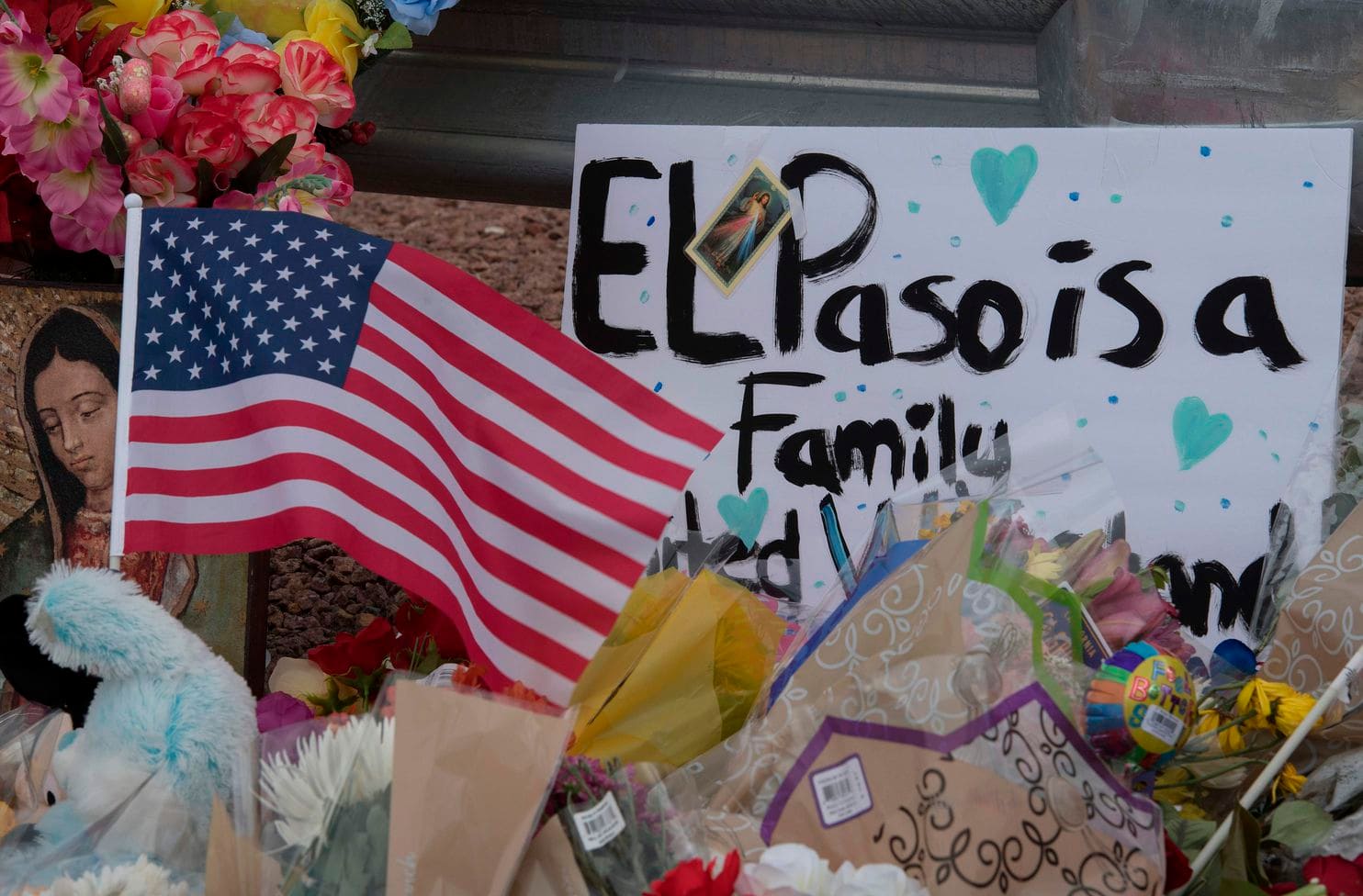

The El Paso shooter cited immigration, stating fears that Hispanic people were ‘invading’ the US, threatening the political power of white Americans.

The centerpiece of contemporary white supremacy is the belief that white people are under attack from a wide range of enemies: feminists, Muslims, liberals, immigrants, African Americans. Like the alt right, they often blame ‘cultural Marxism’ for their woes. They often subscribe to conspiracy theories that identify demographic changes as existential threats to white identity.

The death toll is substantial: over 175 people have been killed in white extremist attacks since 2011.

This marks a chilling turning point in US history, marking the first time more Americans have been killed by white supremacists than Islamist terrorists since 9/11. Although politicians (like Trump himself) refer to these attacks as senseless, such attacks often coincide with key political events like elections. The British MP Jo Cox, for instance, was assassinated by a far-right extremist in the lead-up to the Brexit referendum. The synagogue shooting at Pittsburgh also took place before US midterm elections.

Although the FBI is currently investigating the El Paso shooting as a domestic terrorism case, authorities are often slow to identify these crimes, which are often classified as hate crimes. According to a report, hate crimes only rank “fifth out of eight priorities, and investigations tend to focus narrowly on a particular attack or attacker”. Sometimes, white supremacist violence is classified as gang crimes, which rank even lower on the FBI’s priority list. In recent congressional testimony, senior FBI officials stated that they were investigating around 850 cases of domestic terrorism in 2019, down from around a 1,000 in 2018.

When hate crimes are not designated as terrorism, the investigations fall to local state and local law enforcement, which are often “ill-equipped or unwilling to properly respond to these crimes.”

In an official statement, Obama called the El Paso shooting as part of ‘a dangerous trend’, comparing them to ISIS and citing white nationalist websites that radicalize these actors.

These networks allow potential killers to interact with each other. They span continents and highlight how the internet and social media has exacerbated the white supremacist problem. For instance, a school shooter in New Mexico corresponded with a man who attacked a mall in Munich.

While Trump is undertaking a number of measures to combat the online proliferation of white supremacist hate, many see him as a significant contributor to the white supremacist problem. “White nationalists think he’s a white nationalist and that’s the crux of the problem,” said Ohio Rep. Tim Ryan.

It’s unlikely that the shootings at El Paso and Ohio will be the last in this strain of white supremacist violence. While these shootings are an illustration of the US’ ongoing problem with white violence- over 2,800 mass shootings have occured since 2012’s Sandy Hook shooting- they also point to the ongoing white supremacy threat that plagues not only the US but the world at large. Banning sites such as 8chan is a good first step, but further vigilance is needed to identify at-risk groups and individuals who are likely to buy into such ideology.

“The FBI has admitted that this is the number one domestic terror threat, but then at the same time federal agencies have been focused on Islamic extremism for so long they are way behind the eight ball on this,” said Heidi Beirich, the intelligence director at the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which monitors hate groups.