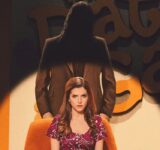

Duped into the sex industry at a young age, a sex worker daringly rises from a pawn to ruling over the same industry using her underworld connections to preside over the 60s gangland Mumbai. A magnetic performance from Alia Bhatt makes this a blazing milestone of her career.

Director Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s film Gangubai Kathiawadi is a riotus, headstrong Hindi crime drama set against the backdrop of the red light district of 1960s Mumbai. It narrates the tale of many a young ambitious women, who were sold off to brothels for a handful of bucks, through the eyes of its protagonist Gangubai (Alia Bhatt) – prostitute turned madam turned advocate and campaigner.

Sometime in the early 1950s or 1960s India, hailing from a well-reputed barrister’s family, a starry-eyed and naïve Ganga is conned by her own lover Ramnik (Varun Kapoor) to elope with the promise of stardom in Bollywood. What happens next, we all know, is that she ends up being the heroine of Kamathipura instead. She’s raped; the film shows her craving for her family yet establishes the end of any possibility that her family will ever accept her or want her back. Gangu accepts her new identify and commences to explore how she and her fellow sex workers can leverage what little power they have.

Loosely based on a real-life woman as documented in journalist S. Hussain Zaidi’s book with Jane Borges, in the nonfiction book Mafia Queens of Mumbai, the film depicts Alia’s character’s transformation from Ganga to Gangu, and eventually Gangubai.

The narrative has a slow buildup- giving the fiery dialogues their own sweet time to build up the powerful moments and leave the desired impacts. However, the narrative does not delve too deeply into any one aspect of Gangu’s life. It captures milestones and boasts some dramatic scenes with clap-worthy dialogues. Yet, when the credits roll, Bhansali’s larger-than-life representation of Gangubai’s eventful life lingers on your mind and piques your interest to know more.

In true Bhansali production style, the music and dance sequences here are top-notch. Every minute of those two and a half hours is worth your money.

There is a certain finesse in how each song is so vibrant and colourfully picturised as a contrast to Gangu standing like a saint in her all-white. The songs, written by the director himself, make Alia Bhatt, the beautiful star, mesh into Gangu, a sensational dancer, with amazing grace, speed and vigor that cement the visual appeal of this film.

Alia Bhatt shows she can get all eyes on her on demand as she slips into the throne of an intimidating boss lady in a world created, catered to, controlled and profited off by ruthless, lustful men.

Ajay Devgan, even in his brief role as Rahim Lala, has a strong footing throughout the film. His extended cameo is inspired by the real-life renowned Mumbai gangster Karim Lala. Indira Tiwari as Gangu’s friend in the brothel and Jim Sarbh as a journalist plays their assigned roles very well. Seema Pahwa put her best foot forward but unfortunately lacked room to shine. Shantanu Maheshwari as Gangu’s love interest does a brilliant job and his bitter-sweet moments with Gangu are what excite the audience and eventually, their heartbreak tears said audience apart.

While the camera sheds light on the darkness residing among Mumbai’s red-light area, it glosses over certain obvious aspects with the quintessential Bollywood extravaganza to make the show palatable to a mass audience. Many filmmakers often use a festive filter in productions of movies on social taboos. Yet Gangubai’s story illuminates the poignant truths about the lives of sex-workers and raises some hard-hitting questions.

No sex or nudity is shown, and the movie doesn’t explicitly manifest the violence that brought most of the girls to become sex workers, but it is implied throughout. Young women and girls, sold by their trusted ones into the sex industry, are imprisoned and raped until they recognize their families and society will never accept them back. The brothel in-charge madams are inhumanly evil who have no sympathy or care for the girls they mint cash exploiting. They are selfish and often seen punishing rebels by intentionally handing them over to the most sadistic clients.

Despite the sex industry being the oldest and largest informal sector of work to exist, the disenfranchised Kamithapura prostitutes have no state-recognised rights; they can’t even open bank accounts. The nearby school refuses to enrol their children and sues them demanding the closure of the entire red-light district. If the explicit indications are not spine-chilling enough, further stories show how commonly women may be assaulted by paying customers. A viral dialogue from this movie makes reference to lustful men having sex with even corpses.

In the midst of this all, Gangu is a female antihero. It filled my heart watching Bhatt draw the same treatment that historically mainstream Bollywood typically reserves for male stars in men-centric commercial dramas: a grand entry, tantalized audience clapping to the hero’s charisma and camerawork that paints a larger-than-life aura to our female protagonist.

Even with the knowledge of this being a biography, it is hard to remember that Gangu really existed, although the storytelling might be aggrandized. Born in 1939 in the Gujurat town of Kathiawar, she was sold at 17 by her newly married husband. It is true that she indeed became a celebrity madam in the 1960s who would rescue and send home many similar-fated girls. However, she was much more ruthless in reality.

It is an open secret that Gangubai Kathiawadi had to obviously sanitize Gangubai’s character in order to make her widely acceptable as a leading lady for a conservative audience.

Bhansali definitely paints a rose-tinted view of Gangu, since he does not elaborate on exactly how she sustained her business if she were, realistically, allowing women under her care to leave at will, and actively opposed forced recruitments into the trade.

The Indian Express reports that there are no contemporary accounts to corroborate the movie’s claims of Gangubai’s saving Kamathipura from being demolished, or the school’s lawsuit or of her meeting the Prime Minister. The movie has, therefore, seen lawsuits from adopted children of the real Gangubai.

While there is much to appreciate about Bhansali’s intricate craft of filmmaking, his signature style drags down the energy of the movie with gaudy, borderline exhausting, obsessive perfection of a series of needlessly attractive looking Bhansali templates. This obsession with visual perfection ends up compromising the humane value of some highly sentimental scenes, such as – when a sex worker dies in childbirth, her colleagues mourn for her like a carefully designed painting rather than functional humans with emotional reactions to watching their friend die.

Another astonishing thing that bothered me in hindsight was casting Vijay Raaz, a cishet man, for playing a transgender person, Raziabai. Bollywood has faced a fair share of public criticism about the politics of casting cis men as trans characters and Bhansali is no alien to it. Despite precedents having been set even in conservative India of casting real-life trans actors to play non-caricatured trans characters, such as Sheethal Shyam in the 2018 Malayalam film Aabhaasam and Meera Singhania in last year’s Bhima Jewellers ad, this decision of Bhansali rubbed the wrong way.

Final Verdict

At the end of the day neither the unmemorable songs, the anthemic costumery or the gripping hook steps stay with us,it is in fact this woman’s overt feminism that sets Gangubai Kathiawadi in a pedestal, different from all the millions of tales of courtesans, madams and pimps narrated by Hindi cinema from its inception. Regardless of factual accuracy and political correctness, by any yardstick, the life of an Indian sex worker who lobbied for the legalisation of sex work in conservative India over half a century back deserves all the celebration this film is bringing along.

Gangubai Kathiawadi is an out and about celebration of the art and anguish of being a woman, and does not hesitate to present itself as a project for all the women of the house.