An Erotic Thriller That Falls Just Short of Being Delightfully Intense

Summary

Halina Reijn’s bold film Babygirl starring Nicole Kidman explores power, intimacy, and self-discovery through a taboo relationship, challenging societal norms and delving into the complexities of desire, identity, and generational shifts.

Overall

-

Plot

-

Narrative

-

Acting

-

Characterization

-

Direction

-

Pacing

In today’s world, many women feel torn between traditional expectations and modern ideals. Some are under pressure to achieve ambitious careers, maintain pristine homes, and fulfill social or familial obligations. Others face constraints, such as unspoken community norms or personal ideals about sexuality and identity. Halina Reijn’s film Babygirl dives into these conflicting pressures and explores what happens when a woman steps outside the roles society assigns to her. By focusing on one protagonist’s desire for more than her safe, structured existence, the film invites viewers to reflect on the complexities of self-discovery, power, and intimacy. Our review of Babygirl examines these complexities, especially from the lens of a Bangladeshi perspective.

From the moment Babygirl opens on Nicole Kidman’s Romy, visibly unsatisfied in bed and then quietly seeking relief through her laptop screen, it’s clear we’re in for a story about desire and the lengths one might go to fulfill it. That longing, as familiar to me as any whispered conversation among friends in Dhaka, is what makes Halina Reijn’s film both startling and strangely relatable for someone like me, now living abroad. Back home, desire has to remain understated, especially if it challenges social norms—being older than one’s partner, being someone’s boss, or just being a woman who dares to crave more than tidy domestic bliss.

At first glance, Babygirl is a story of contradictions. Its central figure, Romy (Nicole Kidman), appears to live a perfect life. She is a successful CEO, spending her days in business meetings, dressed impeccably, with a warm family that includes a charismatic husband (Antonio Banderas) and two teenagers. To all outward appearances, she has achieved success in every conceivable way. Yet the narrative quickly reveals an undercurrent of dissatisfaction. Romy moves through her routine with a sense of restlessness, hinting at a void beneath the polished surface.

In many stories about powerful people, dissatisfaction stems from an external crisis, such as a failing project or a public image threat. In Babygirl, however, the tension arises from an internal conflict. The viewer sees glimpses of Romy’s private turmoil, the feeling that although her life seems unblemished, she craves something intangible—a version of passion or freedom she never dared to claim. She goes through her domestic interactions, shares exchanges with her husband, and ensures her children’s needs are met. Yet deep down, a persistent void remains undefined. This tension sets the stage for the arrival of Samuel (Harris Dickinson), a charismatic and much younger intern, played with a careful blend of confidence and guarded vulnerability. In Bangladesh, such a longing would typically stay locked behind closed doors. But Babygirl throws it onto the big screen with an unapologetic boldness.

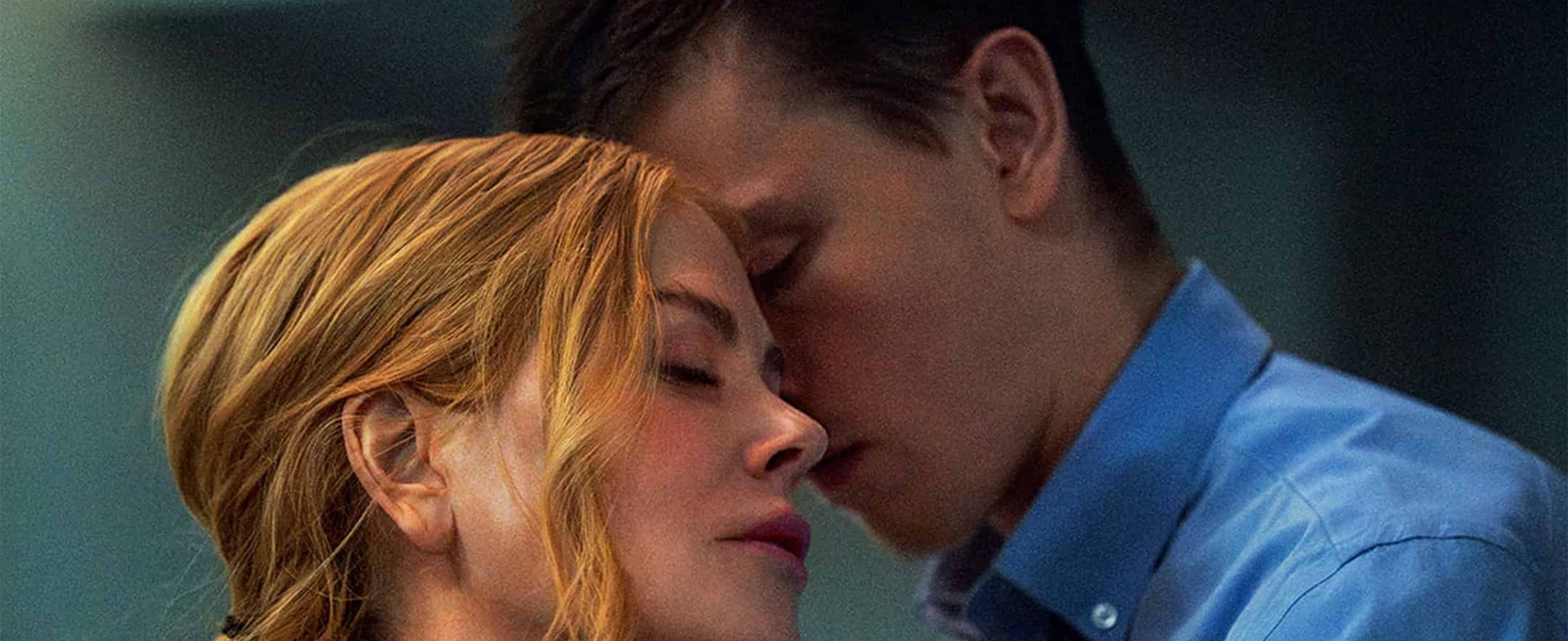

From the moment Romy encounters Samuel, the film establishes unspoken tension. Their first meeting is charged with an attraction that feels laced with potential danger. Samuel is not merely a subordinate in Romy’s corporate structure; he carries an air of mystery, making it clear he is more than a fresh graduate seeking experience. He sends Romy unexpected signals, such as ordering her a glass of milk at a restaurant and whispering “good girl” as he passes. These moments, while minor, signal a shifting power dynamic. They highlight the uncharted territory Romy finds so alluring. In other contexts, such exchanges could seem inappropriate or manipulative. In Babygirl, they become part of the surreal magnetism drawing Romy and Samuel closer together.

As we review Babygirl, it’s easy to imagine the moral backlash that might arise from a boss-intern relationship. Romy is significantly older and wields authority over Samuel, a dynamic that raises ethical red flags in real life. But Babygirl avoids becoming a cautionary tale about exploitation. Instead, it charts the emotional currents drawing these two characters together. Romy is not depicted as a conniving older predator, nor is Samuel portrayed as a naïve boy with no agency. Rather, the film presents them as individuals stepping into a relationship that challenges conventional boundaries. The age and power gap isn’t ignored, but it isn’t the sole focus. Instead, the plot emphasizes their emotional and psychological dynamics.

Viewers from my part of the world might wonder why Romy never seems to fear the gossip and familial judgment that would come crashing down on her if she lived in Dhaka. But Babygirl sidesteps that cultural angle in favor of examining Romy’s internal crisis. The script doesn’t unleash a storm of condemnation, even as her marriage falters. Instead, the emphasis is on how a person’s stifled desires can erupt in unexpected ways—sometimes destructive, sometimes strangely liberating.

One of Babygirl’s most compelling elements is its depiction of Romy’s journey toward self-discovery. The story doesn’t center on guilt or condemnation but on how Romy awakens to desires she has long suppressed. This isn’t a film about moral repercussions, though it acknowledges her choices might invite judgment. It’s about someone who has spent years excelling in every domain—wife, mother, executive—realizing there is a part of herself she has scarcely explored. Romy’s interactions with Samuel bring that suppressed facet to light. Watching them explore dominance and submission is both disconcerting and liberating. Romy begins to uncover aspects of her identity she had ignored or dismissed.

This dynamic resonates with anyone feeling stuck in roles they never questioned. Whether someone has spent years as a caretaker or a model professional, the desire to break routine can become overpowering. Romy’s attempt to break free, while risking her reputation and stability, offers a window into choices that feel simultaneously reckless and necessary. While the film doesn’t lecture, it implicitly raises questions about the cost of burying your deeper yearnings—and how far you might go once those yearnings surface.

Our Babygirl review also acknowledges that the film has its shortcomings. It leaves some real-world complexities underexplored, particularly the ethical implications of Romy and Samuel’s relationship. The film doesn’t deeply delve into what might happen if their affair were exposed or how it could affect the workplace. While secrecy is acknowledged, the narrative remains focused on their private connection. Some viewers might feel the film should have grappled more with these potential consequences. But perhaps this choice is intentional—Babygirl prioritizes the intimate evolution of its characters over broader repercussions.

The film also introduces a parallel narrative involving Romy’s teenage daughter, who navigates her own clandestine affair. This subplot highlights generational shifts in how relationships are perceived, underscoring a culture in flux. While Romy feels guilt and fear in exploring her sexuality, her daughter embraces experimentation with less hesitation. This contrast emphasizes how taboos evolve and how younger generations often question assumptions their parents accept. The daughter’s storyline provides a counterbalance to Romy’s anxieties, offering a broader perspective on unconventional relationships.

Nicole Kidman excels as Romy, bringing emotional depth to a role that could have felt superficial. She portrays Romy with a tension between composure and longing. In every scene, you sense the strain of a carefully constructed life cracking open. Kidman’s ability to convey conflicting emotions gives Romy a complexity that evokes empathy for a woman grappling with an existential crisis.

Opposite Kidman is Harris Dickinson as Samuel, whose performance is pivotal. If Samuel had been portrayed as a shallow plaything for Romy’s fantasies, Babygirl would risk undermining its narrative. Instead, Dickinson imbues Samuel with depth and agency, revealing motivations as complex as Romy’s. He is not simply a pawn in her quest for renewal but an enigmatic presence who challenges her—and the audience’s—assumptions. This reciprocity gives their relationship authenticity, even as the premise raises ethical questions.

Babygirl also explores the tension between private desire and public roles. Many people spend years perfecting a façade that aligns with societal expectations: a successful career, a stable marriage, and a harmonious family life. Yet these accomplishments can feel hollow when accompanied by deep-seated dissatisfaction. Romy’s transgressive choice to pursue gratification outside her defined roles highlights how easily well-constructed identities can unravel when confronted by suppressed desires.

The film examines power dynamics with nuance. Romy is a wealthy authority figure, raising the possibility of exploiting her position. But Samuel’s confident advances and bold provocations suggest he wields a different kind of power in their intimate encounters. This interplay underscores that power is context-dependent—a dominant figure in one arena can be vulnerable in another. Romy’s professional world demands constant control, but her encounters with Samuel allow her to relinquish it. This dynamic invites viewers to question where the line between willingness and exploitation lies.

Babygirl’s explicit scenes don’t feel gratuitous. Each moment of intimacy or manipulation adds to the portrait of Romy and Samuel’s connection. In a society where sexual themes can still provoke controversy, Babygirl takes an unflinching approach. The film uses eroticism to capture the force of a taboo relationship, refusing to condemn desire outright while acknowledging its potential for turmoil.

The film’s empathy for flawed characters is one of its strengths. No one in this story is entirely right or wrong. Romy’s husband is kind and supportive, yet unable to fulfill her needs. Samuel exudes confidence but is not without his vulnerabilities. Even Romy’s daughter, whose secret relationship might be judged harshly, is shown forging her own path in a world full of constraints. This lack of clear antagonists or victims aligns with the film’s broader refusal to provide moral absolutes.

By the time Babygirl concludes, Romy has reached a transformative point. There is no grand resolution or tragic downfall. Instead, there is a quiet moment of self-reflection where she confronts her actions and emotions. The film doesn’t hand down a verdict. It leaves us to wonder whether Romy will continue on this new path or return to her old life, forever changed by her exploration. The courage required to face such questions, particularly for someone who has never ventured so far outside propriety, is what makes the film resonate (resonate).

Babygirl lingers as a cinematic work that avoids moral absolutes. It embraces ambiguity, inviting viewers to interpret its characters’ choices through their own values and experiences. Many films claim to tackle taboo topics but end up glamorizing or condemning them. Babygirl takes a subtler approach, showing the contradictions that arise when people chase desires that clash with their identities. It reveals how quickly the facades we build can crumble—and how challenging it is to piece them back together.

The film also reminds us that stories about forbidden relationships aren’t always about condemnation. Sometimes, they explore the tension between societal constraints and personal freedom. These stories can unsettle us because they reveal how easily powerful urges can disrupt stable routines. The question isn’t just whether we should pursue those urges, but what doing so means for who we thought we were.

Ultimately, Babygirl challenges viewers to empathize with characters who make risky, ethically ambiguous choices. It invites introspection: Where in our lives are we denying parts of ourselves? What desires or aspects of identity are we too afraid to suppress? While the film doesn’t provide reassuring answers, it creates a space to grapple with these questions. That open-ended reflection may be its greatest gift.

By the film’s conclusion, Romy’s image in the mirror captures Babygirl’s essence: the tension between safety and yearning. The film doesn’t resolve this tension neatly but leaves viewers with a story that is messy, haunting, and deeply human. In doing so, it opens a dialogue about how much of ourselves we can hide before we inevitably unravel.

If there’s a single thing Babygirl confirms, it’s that there’s no one-size-fits-all script for a woman’s evolving sexuality—particularly for those who are told they should be “past” their prime. In a society like ours, where an older woman is often expected to set aside her passions and serve as a model of decorum, the film might come across as scandalous or outright forbidden. But the heart of Babygirl is simply this: desire is messy, and no matter how carefully we structure our lives, it can suddenly rearrange them.