A Strong Blend of Historical Fiction with Dark Horror

Summary

Ryan Coogler’s Sinners blends historical drama, Southern Gothic, and supernatural horror, exploring Black Southern life, blues music, and identity. The film’s ambitious storytelling, vibrant characters, and haunting themes create a thought-provoking, visually striking experience.

Overall

-

Plot

-

Narrative

-

Acting

-

Characterization

-

Direction

-

Action

-

Pacing

Ryan Coogler has built an impressive career. He moved from the intense drama of Fruitvale Station to reviving the Rocky franchise with Creed. Then, he directed the cultural milestone Black Panther. With each success, he gained influence in Hollywood. Now, he’s one of the few filmmakers who can bring ambitious, personal visions to life. Sinners feels like the result of that journey—a bold mix of historical drama, Southern Gothic mood, and bloody vampire horror. The film bursts with ideas, beautiful visuals, and deep themes. It’s a stunning, often engaging effort that aims high, even if it sometimes falls short. This kind of large-scale, thoughtful genre film is rare, and it makes you think about its complex ideas long after it ends. Our review of Sinners looks at how the film stacks up to the rest of Coogler’s filmography.

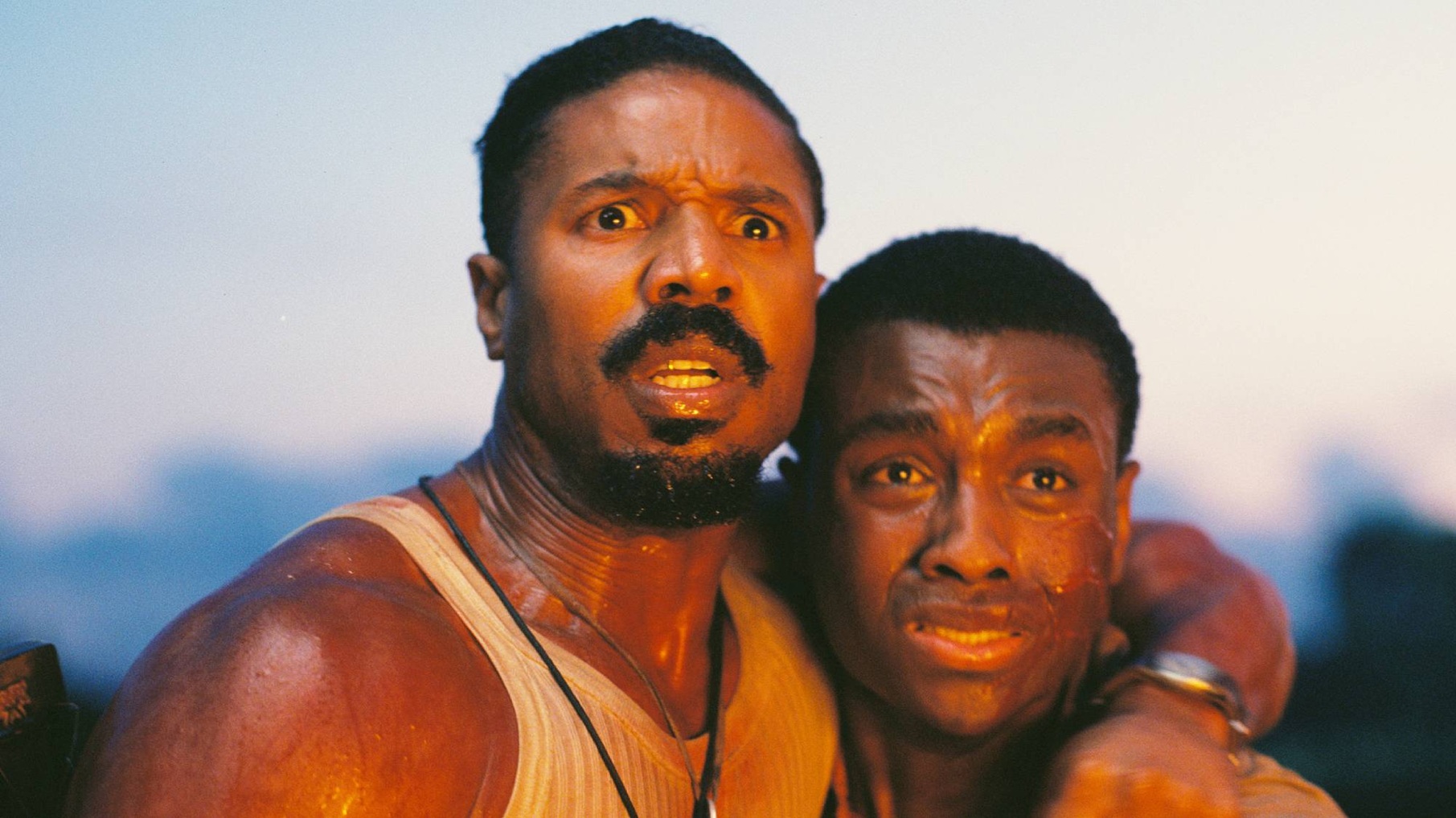

Sinners primarily takes place over one intense day and night in 1932 Clarksdale, Mississippi. The film immediately draws you into its specific world. You can almost feel the Mississippi Delta dust, the constant pressure of Jim Crow laws, and the simmering power of the blues. Two brothers, Smoke and Stack, return to this charged setting. Michael B. Jordan plays both roles compellingly. They aren’t just local boys returning home; they are hardened veterans from World War I and, more recently, from working for Al Capone in Chicago. They found the North just as harsh, calling it “Mississippi with tall buildings.” They prefer facing the familiar challenges back home. Their goal is to use their street smarts and money to open a juke joint. They want to create a place for Black joy, music, and community in a land set against them.

Jordan’s dual performance is impressive, helped by subtle visual effects, but its real strength lies in how he shows the small differences between the brothers. It’s not just Smoke’s cap versus Stack’s hat with gold teeth; you have to look closer. Stack offers a quick, dangerous smile while Smoke remains serious. Stack seems coiled but willing to compromise; Smoke is colder, more calculating. Jordan portrays these differences quietly, making them feel natural. They are two sides of the same coin, shaped by shared experiences but on slightly different paths. They are strong, magnetic figures – smart businessmen one minute, ruthless enforcers the next. Coogler, directing Jordan for the fifth time, uses his star’s talent well. He draws us into their world, making us root for their risky plan despite their violent past.

The film patiently builds this world. It focuses on the details of the twins’ frantic effort to open their juke joint by nightfall. They buy an old sawmill from a hostile white owner whose racism is clear. They order a sign from the local Chinese grocers (played warmly by Li Jun Li and Yao, hinting at the South’s diverse population). They gather supplies. Most importantly, they look for musicians to make the club legendary. This leads them to Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo, perfect in the role), a weary, hard-drinking bluesman whose music carries deep history and soul. They also find their young cousin, Sammie Moore, known as “Preacher Boy” (played with impressive depth by newcomer Miles Caton).

Sammie becomes the film’s emotional center. He is torn between the powerful release of the blues – a talent that seems almost supernatural – and the strict religious expectations of his preacher father (Saul Williams). Sammie represents a direct link to the legends of Delta blues, recalling the story of Robert Johnson selling his soul at the crossroads. The twins give him a guitar supposedly once owned by blues pioneer Charlie Patton, placing him firmly in that revered, perhaps risky, tradition. Is his music a gift from God, a force for freedom? Or is it the “devil’s music,” leading him away from the church? Sinners lets this question hang in the air.

The world of Sinners is filled with memorable supporting characters, each with their own histories and hopes. Smoke reconnects with Annie (Wunmi Mosaku, intense and watchful), a practitioner of folk magic tied to him by past sorrow. Their scenes together pulse with unresolved feelings. Stack confronts his past with Mary (Hailee Steinfeld, showing both vulnerability and assumed confidence). She lives on the white side of town but feels connected to the Black community. We understand Stack likely left her because he believed their love couldn’t survive in a racist world. These relationships, plus Sammie’s shy interest in the married singer Pearline (Jayme Lawson), add layers of adult complexity often missing in horror films. The characters feel real, shaped by life’s hardships and joys.

For much of its first hour, Sinners works mainly as this detailed, character-focused historical drama. If you didn’t know it was a horror film beforehand, you might not guess what’s coming. The cinematography by Autumn Durald Arkapaw is beautiful, capturing both the sunlit beauty and the hidden dangers of the Delta. The feelings of community, struggle, and determined hope are strong. We care about the juke joint’s success, the characters’ intertwined lives, and the sheer power of Sammie’s music.

Then, everything changes. Remmick (Jack O’Connell, sharp and disturbing) arrives. He’s an Irish vampire whose hunger seems both physical and symbolic. His arrival, along with his small group, drastically shifts the film’s direction. He represents an outside threat, first appearing at the home of Ku Klux Klan sympathizers (a Klan hood seen casually in their home is a chilling detail). The film uses some standard vampire rules – needing an invitation to enter, weaknesses to certain items. But it also adds new elements, like glowing eyes and the ability to absorb a victim’s memories and skills through feeding. This power explains Remmick’s intense focus on Sammie. He wants not just blood, but Sammie’s special connection to the past – a connection vampirism seems to have cut him off from.

This sharp turn from realistic drama to supernatural horror might divide audiences. Some will find it thrilling – a bold mix of genres handled with Coogler’s usual skill for exciting action. The vampire fights are reportedly graphic and intense, enhanced by IMAX filming. Others, however, might feel disappointed, as one critic noted. The carefully built realism and character focus seem pushed aside for more standard horror elements. Does the vampire story naturally grow from the film’s themes, or does it feel like a choice made for commercial appeal, possibly overshadowing Coogler’s talent for drama?

The meaning behind the vampires is strong. They aren’t presented as romantic figures but as symbols of the white power structure trying to drain the life from the Black community. They offer eternal life, but it means giving up one’s identity and freedom. This is a particularly cruel offer for characters already fighting for dignity in an oppressive world. Their recruitment methods feel like those of a cult; one creepy scene shows them trying to win converts with a synchronized, mocking Irish step dance. However, some critics felt this symbolism, and Remmick’s own reasons, weren’t fully explored and felt underdeveloped amid the growing chaos. Moments of violence and tragedy sometimes feel rushed, losing some emotional impact because the film tries to cover so much ground.

Despite these potential issues, Sinners remains fascinating both intellectually and visually. The exploration of the blues stays vital. A key scene, praised by critics, shows Sammie’s performance seemingly bending time inside the juke joint. As the camera moves through the dancing crowd, figures from music history appear – a West African drummer, a funk guitarist, a breakdancer, a DJ. It’s a stunning, maybe slightly too direct, visual statement about the music’s lasting power and origins in the Delta.

Coogler doesn’t lecture about racism. He trusts viewers to understand the situation from the historical context. The film explores complex ideas: faith versus folk traditions, the meaning of community, the weight of history, and the persistent search for love and self-expression against huge obstacles. Its willingness to deal with adult themes and relationships also makes it stand out.

In the end, our review of Sinners agrees that Ryan Coogler’s unique vision is on full display, showcasing his hard-earned freedom to create significant, personal films. It feels both grand and intimate – a wide-ranging story of Black Southern life mixed with supernatural fear. It might not perfectly blend its different parts for everyone. Its ambition sometimes seems greater than its reach, leaving some story threads or emotional moments feeling incomplete. It might not fully satisfy those looking only for scares, or those only interested in the history. But its refusal to fit neatly into one box is part of its strength. It’s a rich, complex, and visually striking film that demands thought and discussion. Like the best dramas, it presents a world, asks hard questions, and leaves you with powerful images and ideas that stay with you. Whether it perfectly achieves all its goals is debatable, but the scale of its ambition and artistry is clear.