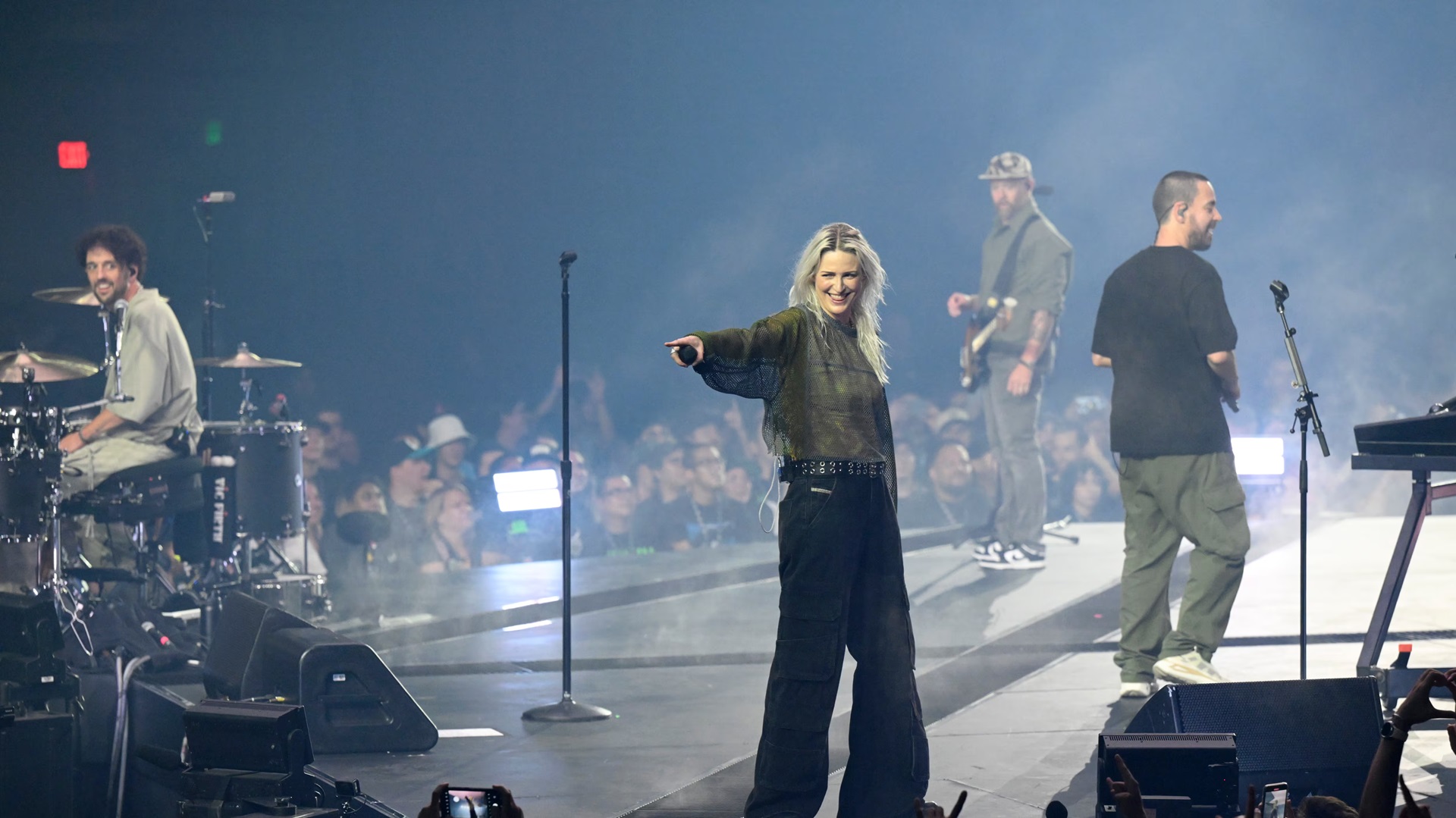

They step onto the stage at a packed arena on a late autumn evening, the house lights still dim, the crowd’s murmurs an anxious hum. There’s a strangeness in the air—an unmistakable sense that everyone is holding their breath. For years, Linkin Park’s story seemed frozen in place, a beloved band caught in a state of shock and silence after the unimaginable loss of Chester Bennington in 2017. Tonight, as the stage illuminates with a haze of blue light, the question of whether they can truly return hovers over every seat and every heart.

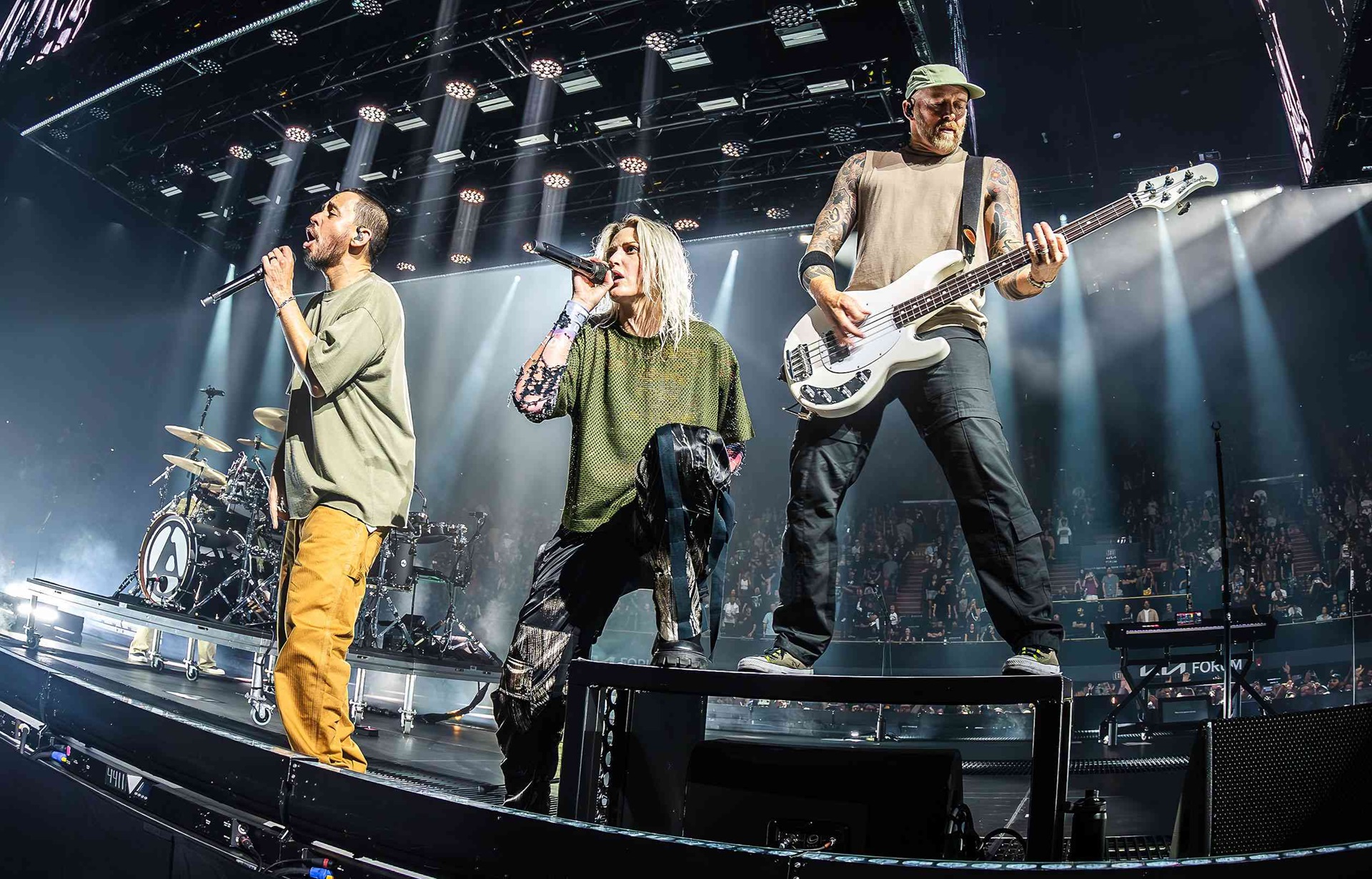

In the half-second before the first note hits, Mike Shinoda glances across at guitarist Brad Delson and bassist Dave Farrell. Joe Hahn stands behind his decks, shoulders tense, waiting for a sign. And at center stage, Emily Armstrong, the band’s new vocalist, closes her eyes and inhales deeply. The air smells of anticipation and fresh paint—the floorboards are new, the backdrop freshly printed, as if even the stage itself had to start over.

This is the world into which From Zero, their first album in seven years, is born. Its title resonates far beyond marketing: it telegraphs a reckoning with emptiness, with the necessity of rebuilding from a scorched foundation. The band’s name has not changed, nor has the collective memory of what they once were—an explosive force that, two decades ago, redefined rock and melded it with hip-hop’s raw pulse. But tonight, and across the 11 songs of From Zero, Linkin Park emerges as something simultaneously old and new, reverent of the past yet carving fresh lines into their sonic blueprint.

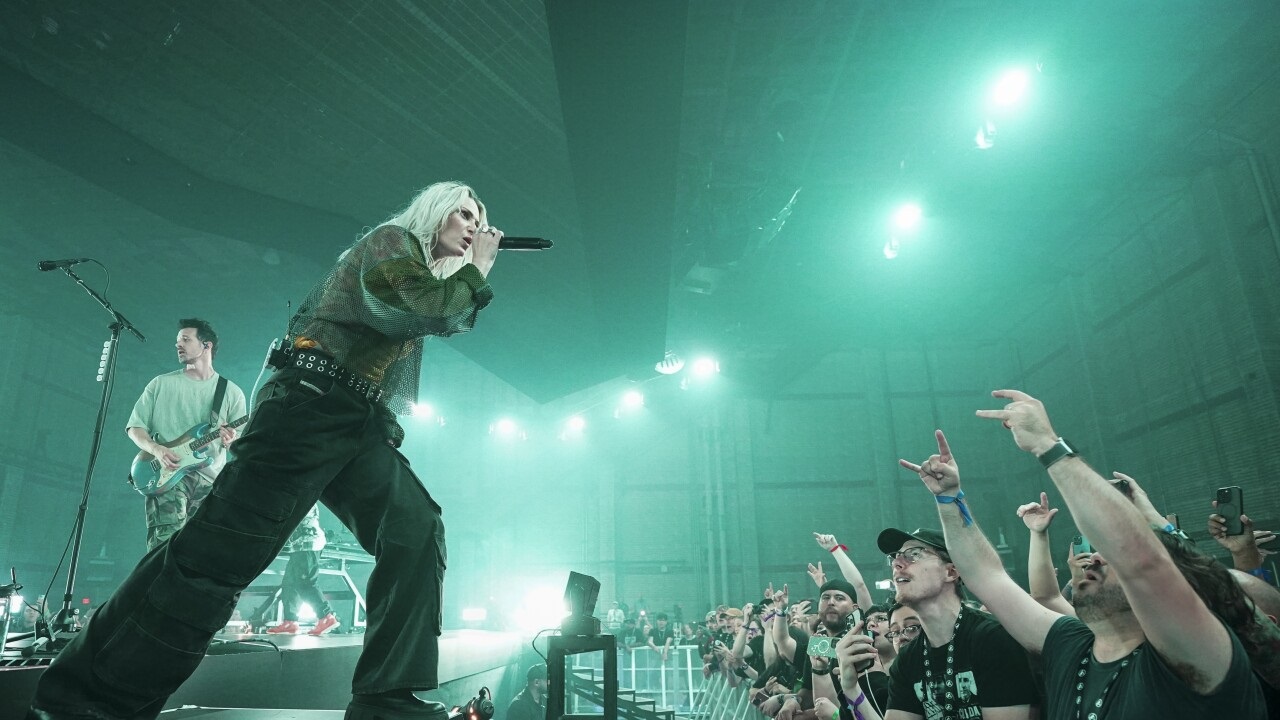

The crowd quiets as the first chords ring out. The journey from silence to sound, from doubt to declaration, has finally begun. And as Armstrong’s voice cuts through the darkness, the story of Linkin Park’s second life begins to unfold before an audience that has waited a long time to exhale.

When Chester Bennington died by suicide in July 2017, Linkin Park’s universe collapsed inward. The force that had once propelled them through packed stadiums and multi-platinum records suddenly vanished.

Friends, collaborators, and millions of fans entered a collective mourning, as if the global music community had lost a guiding star. Within the band’s inner circle, shock and devastation gave way to silence. Without their singular vocalist, without that electric synergy of twin frontmen, the future of Linkin Park seemed unthinkable.

In the months that followed, Shinoda struggled to even set foot in the studio. He picked up a pen, wrote a few lines, and abandoned them. The other members—Delson, Farrell, Hahn—found their instruments eerily quiet. Once so full of creative noise, their rehearsal spaces felt like hollow corridors. They moved through their own separate lives, some tried to focus on family and personal projects. News outlets drew comparisons to Nirvana after Kurt Cobain’s passing: a band so identified by a singular voice, now rendered incomplete. Rumors swirled about permanent disbandment. If anyone pressed Shinoda for an answer, he had none. He only knew that forcing anything—another album, another public appearance—felt like a betrayal, both of Bennington and of the fans’ trust.

Time passed. The world changed. Shinoda poured his grief into a solo record, Post Traumatic, an audio diary mapping the territory of despair. But that project was singular and personal, not a roadmap for the band’s future. The others gave him space. Occasionally, they convened for small private gatherings—no cameras, no announcements. They’d talk quietly about old touring memories, about jokes Chester told on the bus late at night, about riffs that never saw the light of day. The silence between them was heavy but not always painful; sometimes it was just the quiet needed to heal.

It wasn’t until much later—years, in fact—that a kernel of possibility emerged. A melody here, a text message exchange there, a snippet of a demo whispered from one bandmate to another. Nothing concrete. Yet beneath that long dormancy, seeds were germinating, nurtured by the idea that maybe, just maybe, Linkin Park could exist again, not as a replication of what was lost, but as a reconfiguration of what remained.

They waited, never forcing the moment. In this suspended state, they learned patience and acceptance. And when the first sparks of a new era finally appeared, they recognized them immediately. Where previously there had only been absence, a small flicker of light now beckoned them forward.

They first heard about Emily Armstrong through a mutual friend in Los Angeles—a suggestion floating in the ether, nothing more. She was known in certain circles for her raw, dynamic vocal style. Some said she had the ferocity of a storm bottled in her throat. Others marveled at her range: from whisper-soft coos to a near-primal scream. But what captured the band’s interest was how naturally she combined vulnerability and force, how she could channel emotion in a way that felt both deeply personal and universally resonant. Armstrong previously fronted Dead Sara, an L.A.-based rock outfit.

The day Armstrong met the band felt more like a quiet introduction than a formal audition. They gathered in a small studio room in L.A.’s Arts District, a bare space with worn rugs and dim lighting. Shinoda welcomed her warmly, making a point to say this wasn’t a test, just a meeting of minds.

Delson sat cross-legged with his guitar, Farrell hovered near the mixing board, and Hahn leaned against a wall. The mood was careful, respectful, as if everyone knew the gravity of the moment: This was about more than adding a member; it was about daring to speak again after years of silence.

Armstrong didn’t try to mimic Chester. Instead, she sang a few lines of a new melody Shinoda had written—something rough and incomplete—and allowed her own tone to seep into the spaces. It wasn’t about hitting notes perfectly. It was about chemistry, the intangible quality that either crackles or fizzles upon first contact. The band watched her face, her posture, noting how she navigated the emotional topography of the lyric. When she finished, there was a quiet pause. Shinoda met Delson’s eyes, then looked to Farrell and Hahn. Each gave a subtle nod, as if to say, “Yes, there’s something here.”

It took some time to finalize the decision. They discussed it intensely, weighing their reverence for the past against their desire to push forward. Armstrong understood the stakes: stepping into a role once filled by a legend, facing a legacy that might resist change. Yet, the band made it clear she wasn’t a replacement. She would co-front, bring her authenticity, help guide them into fresh territory. Chester’s legacy would remain sacred, not erased or overshadowed, but acknowledged as a guiding spirit as they charted a new course.

A few weeks later, Armstrong officially joined Linkin Park. There were no grand announcements or immediate recording sessions. Just a simple understanding that the silence had been broken.

A new voice had entered the void, and in her wake came a renewed sense of purpose, a conviction that the band was ready to speak again—this time, with a story that belonged to all of them.

In the summer leading up to recording From Zero, the band rented a tucked-away rehearsal space in a converted industrial complex near downtown L.A. It was a space with exposed brick walls, a hint of sawdust in the air, and minimal distractions. Here, they allowed themselves the freedom to experiment without a ticking clock. Some days, Delson fiddled with riffs while Hahn layered loops of subtle electronic textures. Other days, Farrell refined basslines that seemed to vibrate with quiet urgency.

Armstrong, now integrated into the circle, worked closely with Shinoda. They might spend hours discussing a single verse: what emotional truth it should convey, how the words should land. On a scratched-up whiteboard, they scrawled lyrics, crossing out clichés and circling phrases that felt honest. The band listened to early-2000s Linkin Park hits to remind themselves of their DNA, but they also sampled tracks from outside their comfort zone—trip-hop instrumentals, acoustic singer-songwriter records, even classical music. This was not about nostalgia or replacing the past; it was about weaving old threads into a new tapestry.

When they hit their first creative roadblock, Shinoda proposed something unusual: a series of small, unannounced international shows. These were in tiny venues, in countries where English wasn’t the primary language—places like São Paulo or Prague. The idea was to test the new material live, to see how it resonated with strangers who had no expectations. In these intimate performances, Armstrong pushed her voice, daring it to break, to find limits. The band observed the audience’s faces, gauging their reactions not by cheers alone, but by the hush that falls when people are genuinely moved.

Returning to L.A., they carried these impressions into the studio sessions that followed. A sense of collective intention emerged. The album would tell a story: acknowledging voids and darkness, then illuminating paths forward. Producers stepped in, helping polish the raw diamonds into final tracks. Engineers teased out subtle sonic layers. They debated over track order late into the night, leaning on instinct and storytelling logic. Each decision was measured, purposeful, guided by the principle that From Zero should neither deny the past nor be shackled by it.

By the time they wrapped recording, exhaustion mingled with satisfaction. They had built something cohesive and sincere from the rubble of grief and silence. From Zero wasn’t just an album—it was a testament to collaboration, a symbol of reemergence. Standing in the half-lit studio, Armstrong and Shinoda exchanged tired smiles. They had forged a new language for Linkin Park to speak, and soon the world would listen.

For Mike Shinoda, this new era began with acknowledging a truth he couldn’t escape: he was older now.

He was a hip-hop artist nearing 50, a veteran whose formative years were etched into a genre that often prized youth and immediacy. He had lost a friend, a co-leader, and spent years grappling with the hollow ache that remained. Yet he found himself still compelled to write, to rap, to sing. As the sessions for From Zero unfolded, Shinoda’s personal journey became central to its narrative core.

His rhymes, once marked by the angst of youth, now carried the weight of lived experience. On tracks like “Two Faced,” his words trembled between accusation and confession. He was no longer just telling stories of personal struggle; he was processing real-life trauma in real time. “Last time, you told me it wasn’t true,” he raps, circling memories of denial and confusion, calling out across a void. It’s an unresolved dialogue with a past that can’t answer back.

Elsewhere, Shinoda leaned into vulnerability. On “Good Things Go,” his voice wavers as he admits, “This is just feelin’ like it’s not that serious, starin’ at the ceiling, feeling delirious.” Age had tempered some of the raw fury of early Linkin Park, but it hadn’t dulled his honesty. If anything, time deepened it. He examined grief as a dynamic emotion—one that evolves, haunting certain corners of the mind, retreating, then resurfacing in unexpected ways.

He saw Armstrong’s presence as an invitation to reflect and adapt. Here was a younger vocalist stepping into a legacy shadowed by loss, carrying her own uncertainties but confident in her craft. Together, they bridged eras and emotions. If Shinoda’s voice was a scarred memory, Armstrong’s was a spark of renewal. Their interplay allowed him to ease at times, to let her carry the fury or the fragility, depending on what the music needed.

In conversations, Shinoda often described From Zero as a dialogue with absence. He knew they could never fill that void, but they could respond to it. And in responding, he found new purpose: to transform pain into sound, isolation into a shared chorus. Standing at the threshold of this era, he embraced complexity, ready to guide the band he helped found into a future that honored its past without being imprisoned by it.

For decades, Brad Delson, Dave Farrell, and Joe Hahn had formed Linkin Park’s instrumental foundation. They were the structure beneath soaring choruses and breakneck verses. Now, with Armstrong’s inclusion and the band’s redefinition, their chemistry felt all the more essential. They couldn’t simply repeat old patterns; they needed to adapt, to innovate, to allow new voices to shape the sound.

In a dusty rehearsal warehouse, they pieced together the instrumental scaffolding of From Zero. Delson’s guitar lines were warm and resonant, occasionally nodding to the past but never lingering there. Farrell’s bass ventured beyond familiar grooves, sometimes guiding melodies instead of following them. Hahn introduced subtle samples and textures, small sonic puzzles that rewarded close listening. Together, they navigated fresh arrangements that spoke to now, not then.

Into this dynamic stepped Colin Brittain, the new drummer. He brought a crisp, urgent style that revitalized their sound. On a track like “Casualty,” Brittain’s drumming didn’t just keep time; it spurred each instrument forward, daring them to find new heights. He listened intently before offering suggestions, unafraid to propose changes. His presence gave the band permission to experiment, to believe they could evolve without forsaking their identity.

During long afternoon jams, they rediscovered their collective voice as instrumentalists. They played snippets of older hits—songs from Hybrid Theory or Meteora—to see how their chemistry might reinterpret those anthems.

Instead of feeling haunted, they felt empowered. Yes, these songs held memories, but the band realized they could still sound vital. Even their legacy tracks breathed differently, as if to say: We’ve learned from the past, and we’re still learning.

By the time they recorded final takes, the interplay between guitar, bass, turntables, and drums hummed with renewed purpose. It wasn’t a legacy act trapped in amber; it was a collective energy that had survived loss and silence. Their music became a scaffold on which Armstrong and Shinoda layered their vocals, a tapestry woven from threads both old and new. In that tapestry, Linkin Park’s spirit—resilient, evolving—remained undeniably intact.

When fans press play on From Zero, “The Emptiness Machine” greets them first. After a tense, brooding intro, Armstrong’s voice emerges: “I let you cut me open, just to watch me bleed.” The intensity is immediate, a challenge and a welcome. The band acknowledges old emotional landscapes—the numbness, the heartache—while forging a fresh path. This track declares: We have survived something tremendous, and we’re not afraid to show our scars.

“Casualty” intensifies these themes. Armstrong’s scream shreds through the chorus, a nod to the vulnerability Chester once embodied. Yet here, it’s her own release. The idea of “putting on her screaming pants” fades from humor to necessity. The track confronts how easily we become casualties of expectation. It asks the listener to bear witness, without flinching.

“Heavy Is the Crown” slows the pace. Armstrong’s voice hovers between whisper and wail, capturing the suffocating weight of fame and legacy. For the original members, this is deeply personal—they’ve felt these pressures. The guitar tones are subtle, the rhythm section patient. Reinvention can be quiet as well as dramatic.

Then comes “Two Faced,” where Shinoda’s verses linger at the edges of old wounds. “Last time, you told me it wasn’t true,” he raps, the line echoing with frustrated longing. It’s neither accusation nor surrender, but a dialogue seeking honesty in silence.

“Good Things Go” marks a midpoint. Its mid-tempo melancholy suggests life’s messiness. Shinoda and Armstrong’s interplay is like distant relatives finding common ground. If good things vanish, maybe they can return, maybe reinvented.

Taken together, these tracks trace an arc of loss, defiance, and hope. From Zero is a narrative, each song a chapter in healing and reclamation. The listener traverses emotional terrain scarred by grief and doubt, finding glimmers of light. It’s not neat resolution; it’s permission to move forward, to trust that rebuilding is possible after ruin.

As the final track fades, what remains is continuity unbound from nostalgia alone. Linkin Park hasn’t denied tragedy; they’ve engaged it. They’ve chosen to carry that weight and transmute it into sound and meaning.

Armstrong’s arrival isn’t replacement, but a key. Brittain’s drumming isn’t a footnote, but a catalyst. The shape of Linkin Park’s name has evolved.

In many ways, From Zero is a declaration of courage. It refuses to treat grief as an endpoint. Instead, the band acknowledges that survival can be messy, memory both friend and ghost. By continuing under the same name, they say: Our identity was never one moment. Chester’s imprint guides them, not as a haunting shadow but as emotional truth they carry.

Imagine a backstage scene long after release. A modest venue, a quiet evening. Armstrong warms up, humming. Shinoda sits on an amp case, head bowed. Delson, Farrell, Hahn, and Brittain adjust gear, exchanging quiet encouragements. They know the audience has questions, comparisons, doubts. But as they step onto the stage, they have clarity and intent.

The cycle of grief and healing continues, forging new links between silence and sound, memory and creation. Each performance weaves old and new into one thread. The band’s scars remain visible, but so does their resolve. In embracing loss and renewal, Linkin Park shows what it means to start over when odds feel insurmountable.

With From Zero, they’ve reshaped their narrative, refusing stasis for reinvention. The future unfolds, open and uncharted. As the first note sounds, they take another step forward, carving their story into the unfolding present.