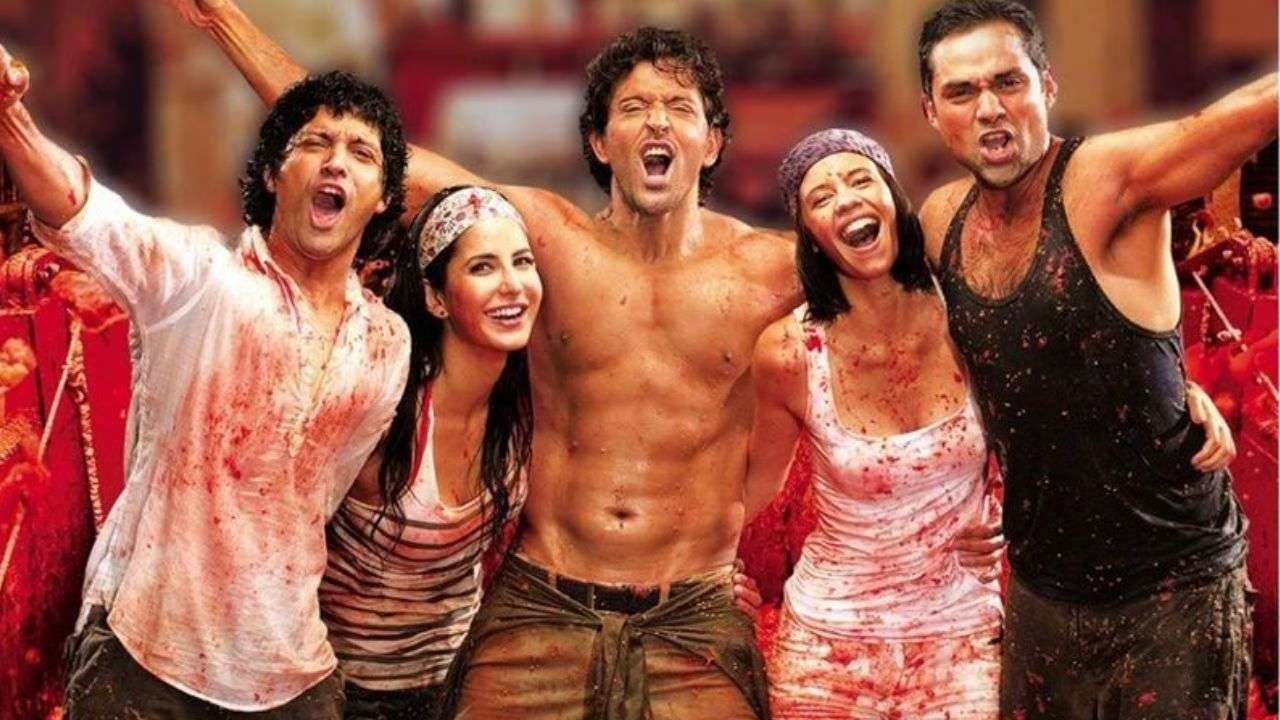

If I were asked to list my favorite Bollywood films, Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (ZNMD) would definitely make the cut. This film, which follows three childhood friends reuniting for a road trip across Spain, is a standout part of Zoya Akhtar filmography, exploring universal themes like friendship, family, love, and self-discovery. But it’s also about three friends affluent enough to afford a month-long European escapade.

This brings us to one of the most common criticisms of Zoya Akhtar’s films: they’re movies for the rich. On the surface, it’s true – most of her work does seem to explore the lives of the privileged and their so-called “rich people problems.” The criticism stems from the fact that India has a huge underprivileged population who can barely relate to the experiences highlighted in these films.

Filmmaking can be a deeply intimate endeavor. The best films often reflect characters, viewpoints, and worlds familiar to their creators. Because we all have different upbringings, someone who grew up as the child of a business tycoon can never truly relate to the child of a day laborer. Their experiences are vastly different. So, when it comes to filmmaking, the privileged artist might struggle to accurately represent the life of someone from a lower social stratum, unless they’ve spent considerable time experiencing that life firsthand.

Zoya Akhtar, undoubtedly had a privileged upbringing. Her father, Javed Akhtar, is a renowned poet and screenwriter, while her mother, Honey Irani, was a famous actress. Zoya studied film production at NYU Tisch, a top-tier university for the arts in the States. This privilege is evident in her first film, Luck by Chance, part of the Zoya Akhtar filmography, where she managed to secure substantial funding and star power despite being a first-time director.

Akhtar herself has acknowledged her privileged background in interviews. Naturally, she excels at highlighting issues she’s observed firsthand and has experience with. This is precisely why her films carry so much weight and depth – she truly knows her subjects and characters by heart. They aren’t hollow shells; they feel real, with their own sets of struggles, and each character experiences natural growth throughout the film.

But has this lens of privilege made Akhtar more limited as a filmmaker? There’s no definitive answer, but it’s worth exploring. On one hand, films like Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara and Dil Dhadakne Do cater to the middle to upper-class, mostly urban populace. On the other hand, her films typically revolve around universal themes such as the exploration of relationships, personal growth, and self-discovery. This universality is a key reason why she’s become one of Bollywood’s most celebrated filmmakers.

Artistic vision doesn’t necessarily need to encompass all experiences; Akhtar’s focus on specific social circles allows for deeper exploration of those narratives. The way she develops characters is unique in Bollywood – her nuanced, rich characterizations are rarely seen in mainstream Indian cinema. She’s certainly made good use of her resources to show a different side of the rich in India – concerned with purpose and identity.

Interestingly, many of Akhtar’s films, while set in privileged environments, often include a critique of that very privilege. Made in Heaven exposes the hypocrisies often hidden behind the glitzy facades of elite weddings.

Does this self-awareness sufficiently address the issue of limited representation, or does it still fall short of truly diverse storytelling?

It’s important to consider Akhtar’s work within the broader context of Bollywood. Compared to many mainstream films that present glamorized, unrealistic portrayals of wealthy lifestyles, Zoya Akhtar’s movies offer a more grounded, albeit still privileged, perspective. She’s also been instrumental in pushing for more women-centric narratives in an industry often criticized for its male-dominated storytelling.

Throughout her career, Zoya Akhtar has shown growth in the scope of her storytelling. Gully Boy explores the life of an underprivileged youth who must overcome numerous hurdles to achieve his dream of becoming a rapper. This shift reflects her interest in becoming a more diverse filmmaker and suggests a willingness to expand her narrative range.

On the international stage, Zoya Akhtar’s films have been praised for offering a window into contemporary Indian society. However, this raises another question: Does the focus on urban, affluent India in her films provide a limited view of the country to global audiences?

While it would be ideal for all walks of life to be more accurately represented in Indian cinema, we shouldn’t necessarily pressure one filmmaker to encapsulate it all. After all, we all have our strengths, and by playing to hers, Zoya has given us some of the finest films Bollywood has to offer – no small feat, regardless of one’s background.

Perhaps the question shouldn’t be whether Zoya Akhtar’s filmography is “too limited,” but rather how her work fits into the larger world of Indian cinema. In an ideal scenario, the industry would have room for filmmakers exploring various segments of society, with Akhtar’s nuanced portrayal of urban, affluent India being one important piece of a diverse cinematic landscape.

Ultimately, this discussion highlights the need for a multiplicity of voices in cinema, each contributing their unique perspective to create a richer, more comprehensive portrayal of India’s complex society. While there’s always room for growth and broader representation, Zoya Akhtar’s contributions to Indian cinema remain significant and worthy of appreciation. Her ability to craft compelling narratives and complex characters often transcends class boundaries, proving that her talent isn’t confined to portraying only the upper echelons of society, nor is it “too limited.” And as long as she keeps exploring these different paths and bringing us new stories, we’re all excited for her next endeavors.