Whenever I think of this concerning question after Sheikh Hasina’s autocratic regime came to an end on August 5, I am always taken back to the conversation I had with a friend that day. After hearing the news about Hasina’s resignation, I immediately called a friend who had always been exceptionally vocal against the previous regime. The conversation started with jubilations and ended with me asking about his father’s job, which led to even more cries of joy.

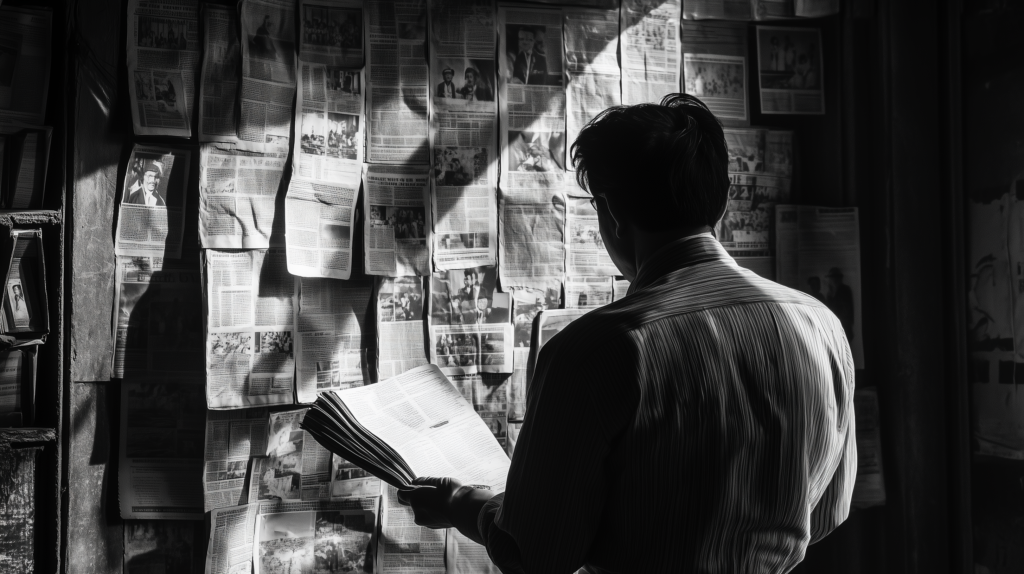

His father was a very competent and well-known journalist before the regime began. A journalist like him had been forced to stay out of work for the last 6-7 years due to the Bangladesh Awami League’s intolerance of criticism. This wasn’t just one man’s story but echoed the struggles of many who aspired to become journalists, only to face oppression instead. The despotism even affected their families, who relied on them as the sole breadwinners. As a journalist or writer, you either conformed to the Awami League’s principles or lost your job.

There was no freedom of expression during the past regime, especially not for print media. In April 2024, the U.S. Secretary of State explicitly mentioned in a press briefing that Bangladesh had some of the most draconian laws for journalists, comparable to those in North Korea, China, and neighboring India.

Many journalists and entire organizations were victims of harassment, extrajudicial procedures, and oppression under the Digital Security Act (DSA). This law, which came into effect on October 1, 2018, became the primary tool to stifle dissent and freedom of expression. Section 57 of the act made it legal to prosecute anyone who published “fake” or “obscene” content online. All the sections of the law effectively eliminated any room for criticism of the ruling Awami League.

Moreover, the decision of whether content was vulgar, fake, treasonous, or defamatory rested solely with the Director General of the DSA division, as stipulated in Section 8 of the act. This role was nothing but a puppet position for the despotic ruling party, used to bring charges against any and all criticism. By 2023, over 7,000 cases had been filed under this law, with more than 60% of those cases initiated by law enforcement agencies and pro-government institutions.

These phantom prosecutions were just the beginning of the oppression faced by journalists. By 2018, most print media had expanded online, and the DSA was used to prosecute journalists for their online content. Whether you wrote for a newspaper, maintained a blog, or even made cartoons, if you lived in Bangladesh, you were likely to be tracked down by the DSA authorities.

This oppression often led to extrajudicial actions. The well-known case of the murdered journalist couple Sagar Sarowar and Meherun Runi, and the death of journalist Golam Rabbani Nadim at the hands of Awami League militants, are just two examples.

Many others were kidnapped by the ruling party. The list of victims goes on, and the most tragic part is that no one could speak out against it. You could look at the only child of Sagar and Runi, Megh, with teary eyes, but you could never demand justice. Those who did were silenced—either imprisoned or buried under heaps of legal cases.

The impact of these injustices didn’t stop with the journalists themselves; their families also suffered. Families continued to speak out in pursuit of justice, but how can you cry for justice when the system itself is designed to suppress you? Despite outcries from the journalism community, the families of the victims also endured systematic oppression, struggling to survive under the weight of these unjust laws.

As a result of this strict suppression of dissent, the media had no freedom. Standing up to the ruling party meant meeting the fate of Amar Desh or Dainik Dinkal. Remember them? When was the last time you saw them? Exactly. These newspapers were red-flagged for allegedly spreading propaganda or being an outlet for the Bangladesh Nationalist Party.

Some newspapers survived, but their journalists were picked off one by one. There was a massive void of information. Everyone knew it, but no one could speak out. Consequently, the system in place continued to suppress freedom of expression, comfortably wielding its tools of oppression.

After August 5, readers breathed a sigh of relief, as did writers. Headlines were no longer misleading, readers were no longer left with more questions than answers, and most importantly, the truth prevailed. For 15 years, journalists had their hands tied, forced to navigate the fine line of censorship while writing.

The days of stifled expression are over, but the wounds of the past are still fresh. Lives were lost, and families still carry the trauma of 15 years of oppression.

This hard-earned freedom came at a great cost and must be protected with vigilance, with each of us asking questions, even when discouraged from doing so.