The big-screen adaptation of Colleen Hoover’s best-selling book It Ends With Us deals with heavy themes like domestic violence and childhood traumas, except it fails to do so. That’s the first line you need to know before you hit the theaters for it. The film’s simplified and romanticized depiction of the toxic relationship misses the mark in terms of accurately conveying the complexities of such grim situations.

Hoover’s work is acclaimed for combining dramatic storylines with intense emotions, but when these elements are placed in a story about domestic violence, it reveals Hoover’s limitations as a writer—though millions of readers might disagree. Her books are also heavily criticized for romanticizing toxic relationships, cheating, and harmful stereotypes. It Ends With Us makes an attempt to address the origin’s inconsistent tone, and there are some promising moments. Yet, it remains shackled by the confines of Hoover’s writing style and the contentious themes that pervade her work.

The story follows Lily Bloom, played by Blake Lively, an aspiring florist who decides to start her life afresh in Boston.

Lily is a sweet, quirky girl, allowing viewers to easily relate to her. However, the film’s predictable “regular girl meets the perfect guy” cliché, which is common in Hoover’s work, limits Lively’s performance.

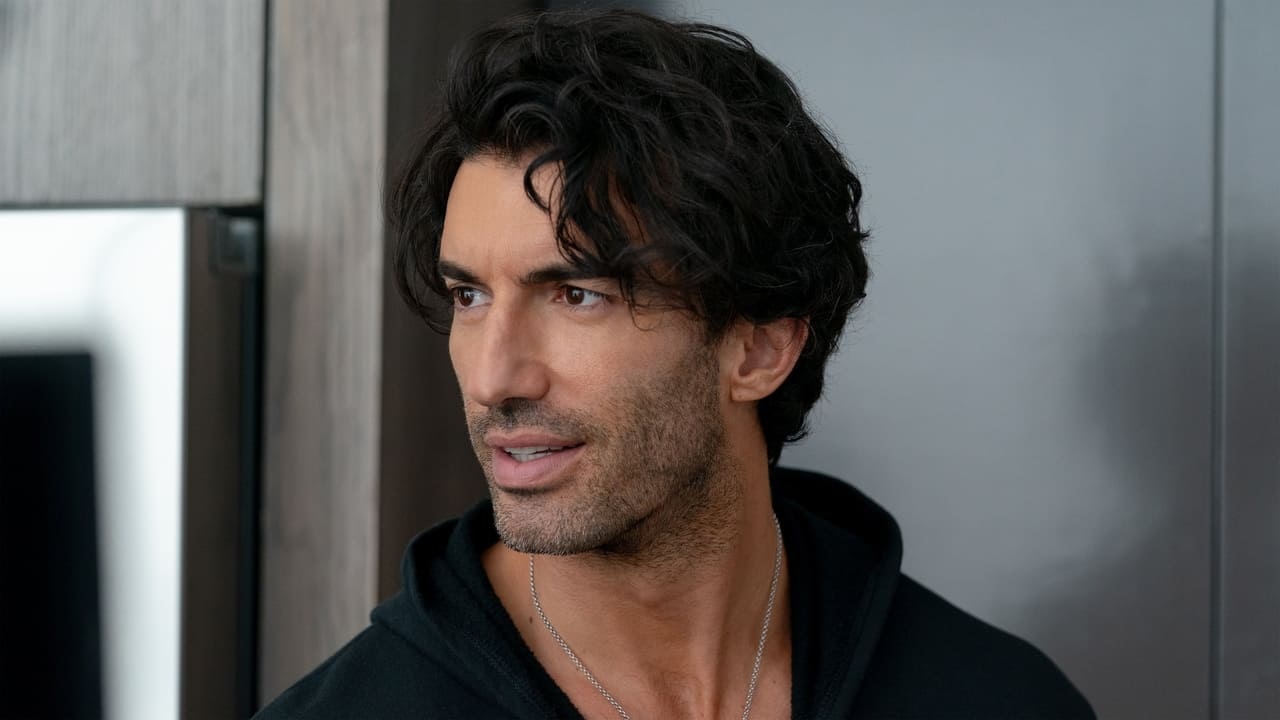

Lily grew up in an abusive household and is now struggling with mixed feelings following her father’s death. She meets Ryle Kincaid, played by Justin Baldoni, a handsome neurosurgeon who initially gives Lily a sense of comfort—giving her all the reasons to ignore his red flags.

Up to a point, It Ends With Us follows the classic romantic melodrama pattern—a rollercoaster filled with passionate romance and periods of confusion. This is where the audience views a textbook pattern of trauma bonding—one of Hoover’s book’s strengths, as it accurately depicts the reality that abusive partners often appear charming and perfect on the surface. They conceal their violent impulses with manipulation and promises—much like Ryle did. Because of this, it can be tough for victims—even those who know the warning signs—to identify the abuse.

Lily’s experience with domestic violence is gradual and subtle, followed by love bombing. She attributes the first incident, a minor injury, to an accident that could have happened to anyone. Ryle’s violent behavior worsens over time, but his frequent blurring of boundaries and excuses make it difficult for Lily to grasp the full gravity of his abuse.

The movie does a good job of capturing this reality by emphasizing how domestic violence is often overlooked until it reaches a critical stage.

As Lily decides to date Ryle, we are introduced to Atlas Corrigan (Brandon Skelner), a love interest from her teenage years. We see flashbacks from their teenage years and the lingering spark between the two. When Atlas senses something is wrong, he confronts Lily and asks her to leave Ryle, eventually starting a fistfight with Ryle in public. Lily’s struggle against abuse and her path to healing gets sidetracked with Atlas’s involvement. The increasing focus on the conflict between Ryle and Atlas makes it appear that domestic violence is being used as a plot device to draw the female protagonist from one man to another, rather than as a central issue.

The biggest inaccuracy is how easily Lily is able to leave once she realizes she’s being abused. Professionals working in the field of domestic violence counseling express concern about It Ends With Us simplifying the depiction of leaving an abusive relationship. Given the theme, the project should have shouldered the responsibility of educating the audience on the grim struggle of a domestic violence victim and why leaving just cannot happen overnight. Its job was to raise empathy by visually portraying the moral dilemma of loving an abusive person and the residual consequences of living with him and daring to leave him. Yet, it did the opposite.

Lily was able to peacefully split from her husband after a single conversation, whereas survivors of domestic violence often face numerous instances of stalking, gaslighting, harassment, threats, and even violence. Neither do we see her facing any custody battle, social isolation, or notable socio-economic problems commonly faced by survivors.

Her financial independence (from her singular flower shop) and the support of her community, especially from her best friend, who happens to be Kincaid’s sister, eased Lily’s departure. We do not see either Ryle or Alyssa struggle to accept reality or at least have a moral dilemma leading up to it: a moment of guilt, selfishness, gaslighting, delusional positivity, or pleading with Lily—traits abusive narcissists are infamous for manipulating their victims with. Both of the siblings are kings of self-awareness who absolutely respect Lily’s epiphanies and boundaries. Survivors have every reason to be disappointed by the film’s utopian portrayal of Lily’s escape, which may seem unrealistic compared to their own lived challenges.

Hoover’s female characters are commonly very stereotypical and one-dimensional. Even Lively’s lively performance fell short of bringing life to Lily. The complexity of the male characters—including the apparently kind Atlas—made them more interesting, though this doesn’t excuse their violent behavior. Meanwhile, Lily felt like an empty shell of a woman, simply a reflection of the men’s flaws rather than being a fully explored character. She remained a distant figure till the end of the movie, whereas the male leads, in spite of their violent tendencies, felt more alive.

The other few female figures in Lily’s life were also underdeveloped, their roles limited to serving as plot points. The relationship between Lily and her best friend Alyssa (Jenny Slate) was unexplored, with Alyssa’s character primarily used to provide context to Ryle’s behavior.

Lily’s mother (Amy Morton) was mostly ignored, confined to the cliché of a loving but helpless parent, undermining the concept of abuse as a cyclical problem affecting multiple generations in families. Jenny Slate and Hasan Minhaj‘s comedic talents are put to good use in the film. Their comedic timing and ability to portray deep emotions with a dash of irony make them suitable for the almost absurd nature of the movie.

The marketing campaign for the film was also a catastrophe. For those unfamiliar with Colleen Hoover’s books, the trailer could easily mislead them into believing it was a lighthearted rom-com. The public feud between the film’s leads, Baldoni and Lively, dominated the news during the press tour, overshadowing the film’s serious themes. The film’s crew, except Baldoni, tried to position the film as a fun summer watch. Blake Lively, who portrays a survivor of domestic violence, seemed tone-deaf and out of touch when answering questions about the topic, focusing instead on promoting her hair products line and outfits. Her beverage brands, Betty Booze and Betty Buzz, were also promoted through absurd events like Betty Blooms pop-up, featuring drinks inspired by the movie. This insensitivity further undermined the film’s credibility and its ability to address the serious issues.

It Ends With Us strives to be a film that explores the insidious and transgenerational nature of domestic violence and the ways in which love and good intentions can blind us to warning signs. It also aspires to be a glittering romance about a small-town girl making it big in the city, tangled in a love story between two men. The film ultimately falls short, descending into a soap opera, largely due to the shortcomings of the book itself.