For years, I haven’t been a practicing Hindu. My relationship with my faith is a little hazy; like any awake person, I have my doubts. My name, ‘Puja’, is an automatic give away as to what my religion is. The name is of Sanskrit and Indian origin, meaning “prayer” or “worship”, and is a common word used during Hindu religious festivals and celebrations. Living in Bangladesh and meeting different kinds of religiously inclined people, it suffices to say I’ve faced my fair share of offensive comments, motivation to convert, and the occasional mocking about cows. I’ve grown immune to it as verbal mockery comes with being a minority in this country, and it’s safer to not retaliate at times. Despite my distance from my faith, I was deeply disturbed by the October 2021 temple desecrations and the conflict that followed this insinuation.

I might not get as excited during Durga Puja and other celebrations as I used to when I was younger, but I’m quite aware of the traditional and sentimental values most Hindus hold for these festivals, and I respect them.

A while back, when I was attending a work event, I met a rather kind Middle Eastern man. We began conversing about life in Dhaka, and he mentioned he was a Muslim. In all honesty and perhaps an allusion to my inner prejudice, I was expecting a negative comment or for him to end the conversation there. However, as the conversation progressed, he appeared to be unaware of the Hindu-Muslim dynamic in Bangladesh and in neighbouring nations. This got me wondering: is the Hindu-Muslim conflict purely a South Asian thing?

Disputes between religious communities are nothing new in today’s world. Almost always, it is a function of which religious community is dominant and which is underrepresented. The countries that come to mind when we talk about the Hindu-Muslim conflict are Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. There are incidents of mistreatment, abuse, and forced conversion of minorities like Hindus and Christians in Pakistan, despite the fact that religious violence there is typically underreported. This brings us to Bangladesh and India, where reports of religious violence are abounding on the internet.

Just as the Hindu community in Bangladesh is a minority and faces religious violence, so does India’s Muslim community. Given India and Bangladesh’s shared history, violent sentiments have transcended geographical boundaries. The Hindu communities in parts of India attacked the Muslim community following the October 2021 incidents in Bangladesh; the Muslims were met with violent chants, vandalism, and other forms of unrest. Some may argue that, as the largest South Asian country, India’s anti-Muslim policies and social marginalization incite anti-Hindu sentiments in neighboring countries. As a result, it perpetuates a cycle of communal violence.

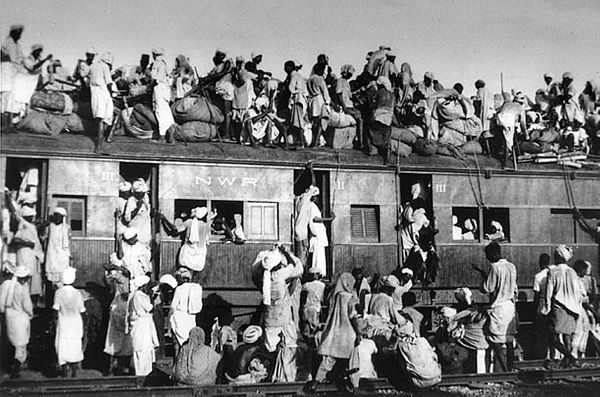

For ages, India has been plagued by Hindu-Muslim bloodshed.

The historical precedent and explosive nature of Hindu-Muslim violence in India should raise concerns due to the small percentage of the Indian population it affects. Furthermore, because India is sandwiched between two Muslim-majority states (Bangladesh and Pakistan), it has a vested interest in managing its violent problem so that it does not devolve into national-level unrest as it has in the past. However, the history of the conflict goes even further back.

In 1679, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb reinstated the hated jizyah (tax on non-Muslims) across his dominion. Saqi Mustad Khan, a court official of Aurangzeb who wrote a reliable biography of the emperor, provided the following justification for the choice:

As all the aims of the religious Emperor were directed to the spread of the law of Islam and the overthrow of the practice of the infidels, he issued orders… “[that] in agreement with the canonical traditions, jizyah should be collected from the infidels… of the capital and the provinces.”

Following Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, the Marathas, who were primarily Hindus, quickly seized control of Mughal territories throughout India while frequently retaliating against the region’s Muslim community. It is safe to say that the Hindu-Muslim conflict in India dates back centuries.

Today, when we talk about religious conflicts, we instantly think of the Middle East as some of the 21st century’s most notorious terrorist attacks and extremism have been linked to groups originating from that region; the conflicts go beyond the stories that are told about them, yet the narratives still have a big impact on how they are waged and what tactics are deemed acceptable.

The temptation to categorize a conflict as “religious” is particularly prevalent for conflicts that are geographically located in the Middle East. If one is interested in Middle Eastern wars, then the concept of jihad, Shia-Sunni disputes, and the religion of Islam and its branches come to mind right away. The conflicts also bring into discussion the Iranian Revolution and the conflict between Israel and Palestine.

In light of the events of the last few decades, there is a notion of Islamic superiority pervading the Middle East. However, it mostly resides with which branch of Islam is right and which is deviating from the original scripture, a difference in beliefs within the same faith, and lastly, about land. The Middle East has a wide range of religions. This region is not just the location of sacred sites for the three main Abrahamic religions—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism—but also for many other faiths, such as Zoroastrianism, the Druze religion, Buddhism, Yaziti, Samaritanism, and the Baha’i faith. This diversity of beliefs can cause disagreement and conflict, which frequently results in religious disputes in the area.

It cannot be stated that religious conflict and violence do not exist in the Middle East. It does. Its circumstances and origins are unique and involve international relations, politics, and the desire to preserve a religion that is over a century old. The widely held belief is that religious motives drive the conflict in the Middle East and South Asia, with minorities bearing the brunt of the fallout and repercussions.

For South Asia, it is nevertheless haunted by a shared history, shaped by the colonial legacy and conceived out of a religious divide. Given these ingrained sensitivities, any tragic incident that takes place in one part of the region would ricochet across borders and have disastrous long-term effects. Although many of us have friends who practice other religions, and we appreciate their choices, the issue is more prevalent in rural and isolated areas. In some instances, xenophobic and extremist sentiments are powerful enough to have the power of legal reformation, leaving minority groups open to legal repercussions. So, undeniably, wherever you are, if you hail from a minority community, every day comes with its own challenges.

Speaking for myself, I still find it difficult to understand how people view me differently from the general population because of my faith, especially because I don’t necessarily follow it (or any other). Not to be confused with having animosity toward religious groups, but rather because I believe religion to be a very private matter. Regardless of personal convictions, it is practically hard to ignore the stigma, dread, and religious tension that pervades the atmosphere. Unknowingly, this can lead to people, like me, internalizing hate crimes and religious mocking. You are pleasantly surprised when you believe you can predict something but are proven to be mistaken.

It gets you thinking: is there an end to this religious tug of war?