Yes, I dream of him. It has been nine years. Sometimes I dream that I’m entering the room and he’s there, sleeping on the living room sofa or the bed, as if he never left. I say, “Where were you? Do you know how much we looked for you?” He replies, “No, you didn’t look hard enough. If you did, you would have found me.” Then I wake up immediately and begin searching for him again.

A dark, empty hallway lined with barbed wire is painted on the wall. Photographs of still water and gloomy skies loom over trees. On the wall hang two headphones, and through one, I listen to a wife desperately holding on to the last slivers of hope for her husband, who left for work one day and never returned. It has been nine years since he disappeared.

Moshfikur Rahman Zohan’s Gum, Jaan O Jobaan is a visceral and bone-chilling exhibition offering a glimpse into the lives of those left behind by the victims of enforced disappearances during the Awami regime.

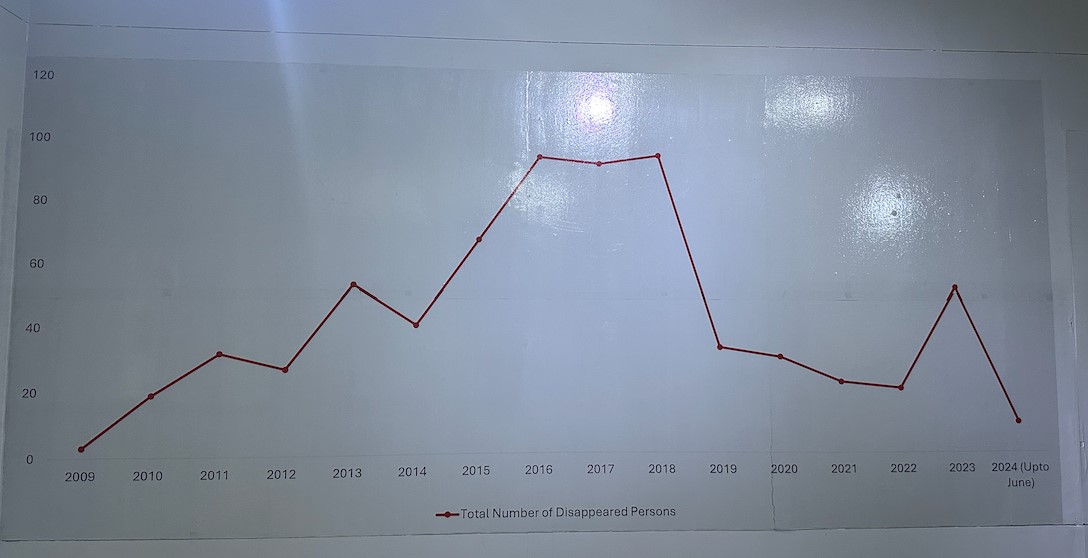

On the eve of August 30th, the “International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances,” the interim government announced a five-member commission of inquiry to investigate the enforced disappearances reported between January 2010 and August 2024. Odhikar, a Bangladeshi NGO, stated that the number of reported cases is 708. However, according to the Capital Punishment Justice Project, between 2009 and 2022, more than 3,000 people with opposing political views have been victims of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances, creating a chain of “political widows” and “political orphans.” If you want to understand the significance of the government’s step toward justice, this exhibition offers that opportunity.

After trudging through streets inundated with at least five times more cars than usual, I reached the exhibition at 11:20 am. The halls were mostly empty, with only two men supervising near the door, perhaps owing to it being a weekday and early in the morning. One benefit of the quiet was that it allowed me to truly absorb the pieces without feeling self-conscious.

The silence helped. Each photograph held a quiet melancholy, and I took the time to fully immerse myself in their stories. It felt as if the photographs had captured the lives that had come to a standstill in the absence of a loved one. Some images showed parents with slumped shoulders, not from age, but from the weight of hope for something that might never happen. Other images portrayed trinkets, pieces of a life once lived, now rendered obsolete. A 2010 edition Nokia phone, probably the latest model when it was last used, now obsolete. A poem written on a note from a loved one, now preserved like a garland. Every photograph told a story.

No parent should have to bear the weight of their child’s lifeless body. But these disappearances don’t even allow for that closure.

“Has it ever occurred to you that he may not come back?” “No, it never has. Not once,” says the weary voice of a father holding onto the last thread of hope.

“The signing of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance is a much-needed first step on the long road to truth, justice, and reparations for victims and their families in Bangladesh. Enforced disappearances are among the cruelest and most dehumanizing human rights violations that have torn families apart in the country,” says Smriti Singh, Regional Director for South Asia at Amnesty International.

Indeed, the most gut-wrenching aspect of enforced disappearances is the lack of closure. If you know someone has died, you can pray for their soul, visit their grave, and find a way to move on, painful as that may be. But with disappearances, the waiting never ends. You flinch at every sound, wondering if it might be them.

Zohan spent years interviewing these families, collecting information, CCTV footage, newspaper clippings, and journal entries, not knowing if they would ever see the light of day, especially given how tightly fascism had gripped the nation. Yet, that did not deter him from carrying out this project. Finally, after the fall of the autocratic government, this exhibition has come to life.

The exhibition runs from August 30 to September 6, from 10:30 am to 6:30 pm at the National Museum in Shahbagh.

Following ex-Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s resignation in early August, at least three individuals who had disappeared were released from secret prisons in the country: Michael Chakma, Abdullahil Aman Azmi, and Ahmad Bin Quasem. They described the inhumane conditions they endured, in places where no sunlight could enter. They were given only 20 minutes in the washroom, with one hand always locked. Sometimes, they were dragged out long before the 20 minutes were up, as Michael Chakma, who was abducted in 2019, recalls.

The newspaper clippings of Anisha Islam Ansha might refresh your memory. They did mine. That girl and her mother fought relentlessly for their father and husband, Ismail Hossain. The police refused to take the case, and the family was subjected to ridicule, with some claiming that Ismail had fled due to unpaid loans or remarriage. This scenario is all too common.

Now, with a step toward justice and the establishment of the investigation committee, there is renewed hope among these families that they, too, may find their loved ones. Every day, they stand in front of the DGFI office, asking for answers. Let’s hope that all the cases are brought to justice and that every parent, wife, and child finds their loved ones or, at the very least, the closure they deserve.