Academy Award nominations are out. After the Golden Globes and Critics’ Choice, Demi Moore is at the forefront of the Oscar race for her role in French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat’s film The Substance. Before her, only Jodie Foster had secured the prestigious award for Silence of the Lambs; Sigourney Weaver was nominated for Aliens in 1987, but she didn’t win. It is arguable whether or not those two even count as real horror, since Silence of the Lambs was a film about a cannibal and a transvestite serial killer, and Aliens was more of a sci‑fi film than a horror film.

The Academy‘s relationship with queer horror has always been complicated. Despite the genre’s ability to push boundaries and explore deep psychological themes, the Oscars have a history of snubbing horror films—despite their strong performances, compelling storylines, and commercial success. After the Academy was heavily criticized for not nominating Toni Collette in Hereditary (2018) or Florence Pugh in Midsommar (2019), this year marked a step in the right direction. In fact, this is a historic year for the horror genre because it is the first time since 1992 that a horror film was nominated in the big categories and not just for hair and makeup, with nominations for Alien Romulus (if available), The Substance, and Nosferatu.

The recognition of horror films, especially queer horror films, in major award ceremonies reflects a broader shift in how the genre is perceived. There have been movies where horror is used solely as a shock factor or for cheap thrills, leading to their artistic dismissal. In fact, it is very hard to do horror right, since the genre is so expansive and its definition includes anything that is out of the ordinary. However, recently, with Jordan Peele’s films showcasing the American social class system designed against the poor and films featuring Black protagonists like Get Out, Us, and Nope—as well as explorations of psychological and generational trauma, cults in Ari Aster’s films, and now I Saw the TV Glow (see below), depicting the struggles of being queer—horror has emerged as a powerful vehicle for social commentary and artistic expression.

As Oscar season draws near and the horror genre finally gains the critical acclaim and recognition it deserves, it is as good a time as any to explore an interesting question that has long intrigued scholars and fans alike: Is the horror genre inherently queer?

Horror has always been widely consumed and adored by the queer community. Often, queer audiences love the goriest of art, label them as their comfort films, and even find dynamics to “ship” in them that wouldn’t come naturally to cishet people. A common example is the Hannibal fandom or the Supernatural fandom, which comprises mostly queer kids. Moreover, Jennifer’s Body—despite starring Megan Fox, an actress desired by many heterosexual men—prompted girls to question their sexuality, rewatching that kiss scene repeatedly. The film’s initial marketing as a straight male fantasy backfired, but it found its true audience among queer viewers who recognized its deeper themes of female friendship, desire, and power.

The idea that horror as a genre is inherently queer is controversial but not new. We will dive deeper into this notion with one of the highest-rated and critically acclaimed films of last year, I Saw the TV Glow (more on this here if available), in a moment.

The entirety of horror, as described by one of the maestros of modern horror, John Carpenter (director of films like The Thing, Halloween, The Fog, and Vampires), can be classified as either the fear of the other—something “out there”—or the fear of something within ourselves, a fear of the self. In that sense, there is something inherently queer about horror films.

There have been numerous discourses on queer-coded horror films. A common example is Frankenstein, where a man essentially creates—or reproduces—another being without any involvement of the other gender. His reaction to the monster he creates can most accurately be described as “homosexual panic.” This idea is further solidified by the premise of the film, in which Victor Frankenstein spends the entirety of the movie trying to find a suitable mate for himself and repeatedly encounters failure.

If we trace the course of horror films throughout history, we can observe what scared people in each era. Horror films have become more abstract in recent times, with “within” themes exploring aspects of generational trauma, cults, disorders, revenge, and relationships, while the “other” is portrayed as multidimensional, unexplainable cosmic beings. Over time, this queer subtext has become less subtle and more arthouse and creative.

In the 2023 film I Saw the TV Glow, these themes are explored brilliantly without once using the labels. Martin Scorsese even called this film one of his favorites of the year. The excellent cinematography and soundtrack are only the beginning of a movie that delivers a gut-punch to the queer experience without explicitly naming it.

Considering Frankenstein as a foundational point, the “monster” is the being that is different from what we are used to seeing—symbolizing conservative heteronormative practices. The monster feels vulnerable, exposed, and scared in its own skin, questioning why it is regarded as a monster when it was simply created that way. The first half of the film showcases its desire to be loved and accepted, a theme that continues in the sequel, Bride of Frankenstein.

Much like queerness—where one feels vulnerable and on edge while yearning to be comfortable in one’s own skin—the monster’s plight resonates deeply. Mary Shelley herself is assumed to have been bisexual, so such implications in her writing are not made in a vacuum. However, one must account for the circumstances under which Shelley wrote the book: her first child had died at less than two weeks old the previous year, and she had recently given birth to another child. Moreover, she was pregnant during the first year of writing Frankenstein. The death of her first child undoubtedly influenced the premise of the book: stitching together dead body parts to create life again.

Although the topic at hand isn’t what the artist had in mind, it is about how the art is interpreted by the audience.

Another significant landmark in horror history is Bram Stoker’s Dracula—the film through which monsters became extravagant and iconic characters. The large cape, gothic gowns and strikingly beautiful portrayal of Dracula in later iterations (see Twilight here for example) have led queer people to associate the character with forbidden desires. Living in the shadows, afraid to “come out into the light,” Dracula is often described as the ultimate “other.” Once he is caught, he is pierced by a stake through the heart by “normal” humans.

Moreover, the way vampires “infect” other humans—transforming them into beings like themselves—parallels the unfounded conservative notion that “LGBTQ is turning our kids gay,” suggesting that because they cannot reproduce on their own, the only way to increase their numbers is by converting children. At its core, Dracula plays on the fear of exogamy, a concept defined by John Allen Stevenson as marrying outside one’s tribe—leaving behind the customs and traditions of one’s ancestors through union with an outsider. This theme is evident in the film: Dracula desires virtuous English maidens and infects them by sucking their blood, representing the fear of societal infection by the other.

It is also apparent that most protagonists in horror films are women. A topical example is the Oscars, where The Substance became the seventh horror film in the 96-year history of the Academy to be nominated. Both Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley deliver phenomenal performances in the film, joining the ranks of other female-led horror films such as Hereditary, Midsommar, and classics like Carrie (see Carrie (1976)) or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (check out here). Even films like Silence of the Lambs and Psycho (more details here) feature strong female leads.

Women are often more inclined toward body horror and gore than men, though in a “comforting” way. This may be attributed to the similar struggles they face due to bodily changes or pregnancy complications, which can sometimes be fatal. These struggles are further amplified for those who are not only women but also transgender.

For many from conservative backgrounds, their first encounters with queer culture come through extreme representations. Queerness is often repressed and regarded as taboo, so when it does emerge, it is sensationalized in headlines that rarely reflect the nuanced reality. A ubiquitous example is transsexuality. While homosexuality is often labeled as sinful or perverse, it is at least acknowledged and somewhat understood. On the other hand, trans people are frequently excluded even within queer spaces, giving rise to terms like trans-exclusionary radical feminism. Trans individuals, who already face significant challenges, have the lowest average lifespans due to the mental and physical toll of such marginalization.

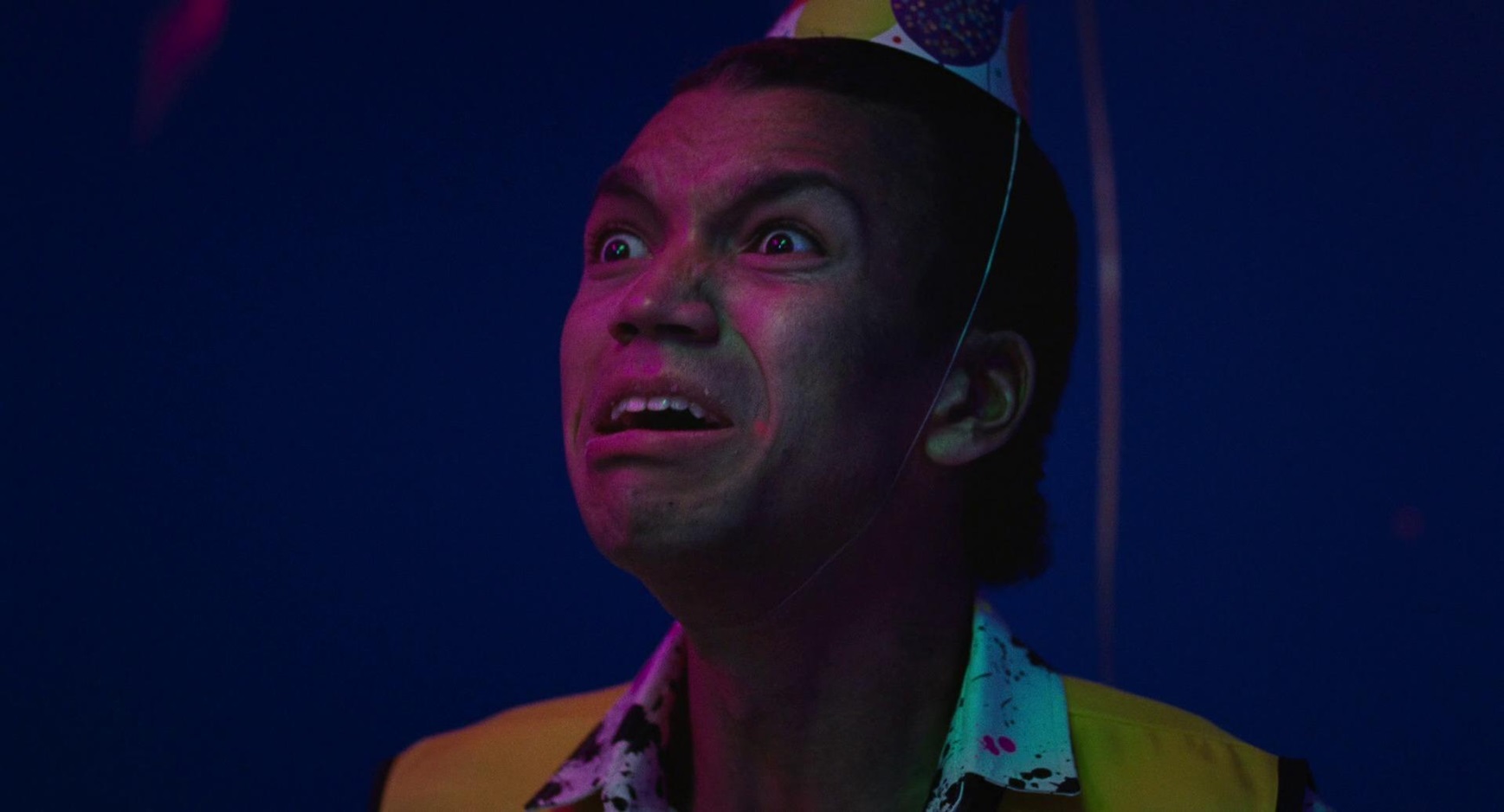

I Saw the TV Glow opens with a beautiful frame of a “boy” transfixed by the neon pink light emanating from a TV. The show, called the Pink Opaque, features two girls fighting Monsters of the Week using their psychic connection to defeat the ultimate evil, Mr. Melancholy (if available), who wants to trap them in a midnight realm of pain and misery forever. Owen loves the show, and despite being only in the seventh grade, when her father finds out, he dismissively remarks, “Isn’t that a show for girls?”—a comment that marks a formative moment for Owen, who realizes that her interests might render her an outcast.

When Owen finds acceptance and understanding from Maddy instead of judgment, she begins to open up—having sleepovers at Maddy’s to watch the show together. Until one day, Maddy breaks down, confessing that the show feels more real to her than real life. Relating to the feeling of being in a closet, Maddy envies those who live the life she desperately wishes for. One of the film’s strengths is that, without ever explicitly stating it, the trans symbolism is powerfully woven into its narrative. The recurring themes of pink and purple and a soundtrack with lyrics like “I’m in the eighth grade, sending grown men grainy photos of my ribcage” underscore Maddy’s inner turmoil. She expresses her desire to escape the reality she finds unbearable—even resorting to burying herself in a symbolic rebirth.

Years later, when Maddy and Owen meet again, Maddy tries to convince Owen to bury herself too, claiming that they were the main characters—Tara and Isabel—of the show, and that once Owen is buried, she will awaken as Isabel in the Pink Opaque. At one point, Maddy even dresses Owen in a dress to drive the point home. Although Owen is initially hesitant, we finally see a version of her that was missing throughout the film: more confident, smiling, and more than just a shell of a person.

What if Maddy was right? What if Owen could become someone else—someone beautiful and powerful—reborn by burying her old self and emerging on the other side of a television screen?

Yet, when it comes time to take that leap of faith, Owen hesitates and walks away from Maddy. She takes a soul-sucking job, and the years pass by in a blur. Until one day, she realizes the terrible truth: her life is a horrible lie. In the middle of a game shop, she screams, “Help me!”—but no one pays attention, and life goes on.

For the social acceptance upon which she built her life, thinking she could handle everything even without being true to herself, her world crumbles, and no one cares.

That haunting realization strikes anyone living a lie—whether in an unsatisfactory job, career, or even in one’s body. For queer people, the implications are even more direct. The film ends with Owen cutting open her chest and seeing the static of a TV, a callback to the dialogue:

“What about you? Do you like girls?”

“I don’t know.”

“Boys?”

“I—I think that I like TV shows.”

In essence, horror movies resonate most with queer people because, much like the genre or the monsters within it, they embody the painful feeling of not belonging. They express our forbidden desires, our deepest fears—fears of abandonment, ridicule, punishment, isolation, or simply being unlovable. We can put on nice clothes and conform to society’s definition of civilized, yet deep down, our true selves remain hidden, waiting for the moment of painful realization.

Throughout the history of cinema, horror has served as more than just a vehicle for fear and entertainment. It has become a mirror reflecting society’s deepest anxieties, particularly those surrounding identity, belonging, and difference. The genre’s long-standing relationship with queer themes and audiences is no coincidence. From Frankenstein’s monster yearning for acceptance to Dracula’s coded representation of “deviant” desires, horror has consistently provided a space where the othered can see their experiences represented, albeit through metaphor and monster. It is time we recognize the immense potential of this genre and the transformative power it holds in helping people find their place in the world and gain the accolades they deserve.