A Thriller about Twin Sisters That Could Have Been So Much More

Summary

“Do Patti” is a Bollywood thriller set in Uttarakhand, blending family drama, social issues, and suspense. Despite strong performances by Kriti Sanon and Kajol, the film’s uneven tone and inconsistent execution hinder its full potential.

Overall

-

Plot

-

Narrative

-

Acting

-

Characterization

-

Direction

-

Pacing

Do Patti opens in the scenic hills of Uttarakhand, a setting that feels both cinematic and quietly foreboding. Its dual timelines and layered themes position it as a modern thriller with old Bollywood charm. Directed by Shashanka Chaturvedi and penned by Kanika Dhillon, the film weaves together familial tensions, societal issues, and a thriller’s suspense, but its ambitions are often tangled. Much like Dhillon’s previous work, Do Patti presents complex female characters, but here, they are surrounded by a plot that feels just a bit too heavy with its weight.

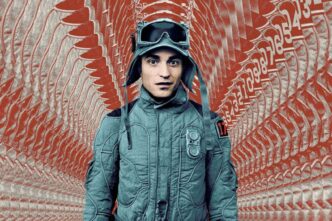

The story centers on identical twins Saumya and Shailee, portrayed by Kriti Sanon in a career-challenging double role. The two sisters couldn’t be more different. Saumya is restrained, almost subdued, finding comfort in the quiet escape of her mountain town life. Shailee, on the other hand, embodies boldness and desire, asserting her independence and yearning to leave the past behind. The film explores the rift that has long divided the twins, stemming from childhood tensions and a sense of favoritism that Shailee felt tilted in Saumya’s favor. As Do Patti suggests, this dynamic is set to combust when both sisters find themselves romantically entwined with Dhruv, a character who, unfortunately, doesn’t quite live up to the magnetic presence he intended to be.

Shaheer Sheikh plays Dhruv, the charming yet volatile son of a powerful politician. He’s meant to serve as the crux of the twins’ rivalry but despite the layers written into his character, Sheikh’s portrayal feels somewhat one-note. There’s a moment in the film where we’re supposed to feel the weight of Dhruv’s entangled emotions and domineering nature, yet these scenes lack the intensity needed to leave a lasting impact. Dhruv’s complexity is crucial for the film’s success, but his character doesn’t provide the emotional depth to anchor the sisterly rivalry around him.

Kajol‘s Vidya Jyothi is a force within the narrative. A gritty police officer drawn into this familial storm, she’s as unyielding as the hills themselves, aiming to uncover the truth about Dhruv and the attempted murder that sets the story in motion. It’s fascinating to see Kajol take on the role of a cop, a character type rarely offered to women of her stature in Indian cinema. Vidya is tough, a bit tired, and, as she proves throughout the film, relentless. Her interaction with Sanon’s dual characters—navigating between Saumya’s quiet resolve and Shailee’s unpredictability—adds a dimension of intrigue and grit to the film. However, Kajol’s Vidya feels restricted by some of the character’s lines, especially the attempt at earthy slang, which doesn’t always sound authentic. Despite Kajol’s inherent charisma and skill, Vidya’s character arc remains flat, more a narrative device than a fully realized individual.

The film’s cinematography by Mart Ratassepp is visually arresting, though the mountainous landscapes do much of the heavy lifting in terms of atmosphere. Uttarakhand is depicted with a haunting beauty, and the framing of these lush vistas reflects the film’s themes of isolation and entrapment. However, due to the grandeur of its setting, Do Patti doesn’t fully capitalize on its surroundings to drive its narrative forward. The visuals serve more as a backdrop than a vital part of the storytelling, making the cinematography occasionally feel ornamental rather than integral.

Dhillon’s script attempts to inject social commentary, particularly on domestic violence and the scars left by societal expectations. A depth in Saumya’s and Shailee’s diverging personalities speaks to the different ways women can respond to trauma and societal pressures. But while Dhillon’s dialogue occasionally cuts deep, her screenplay doesn’t quite measure up.

The film’s tone is inconsistent, oscillating between psychological thriller, family drama, and social message. This shifting tone means that moments of emotional resonance—particularly the underlying theme of domestic abuse—don’t always land with the intended gravity.

What Dhillon does accomplish with the writing is a clear delineation between Saumya and Shailee. Sanon portrays both women skillfully, making their differences clear without relying solely on costumes or dialogue. She brings a particular subtlety to Saumya’s introversion and a volatile energy to Shailee’s rebellious streak, showcasing her versatility as an actor. Yet, the script’s heavy-handedness means that these performances, as commendable as they are, feel somewhat constrained by the predictable dynamics of good twin versus evil twin, a trope we’ve seen in countless Bollywood films.

In the film’s final act, Do Patti makes an overt statement on domestic violence, positioning it as both a personal tragedy and a societal ill. While the message is necessary and powerful, the delivery feels almost didactic, losing some of the nuances that would have made it more impactful. There’s a sense of urgency in Dhillon’s writing to address this issue, but the film’s resolution feels abrupt as if it suddenly shifts gears to become a public service announcement. The narrative momentum built up through Vidya’s investigation, and the tension between the sisters slows to a crawl, leaving the viewer less absorbed in the story than they were earlier.

Tanvi Azmi’s character, Maaji, adds another layer to the narrative, her mysterious air and cryptic remarks offering a hint of suspense. Maaji is more than just a caretaker; she’s a figure who understands the family’s darkest secrets and subtly influences the sisters in ways that are not immediately obvious. However, her character’s role, much like the film itself, is inconsistent, and what could have been a powerful narrative tool for uncovering hidden truths becomes an underutilized plot element.

Do Patti achieve a thriller’s suspense and a drama’s depth in moments. But the film’s struggle to maintain a clear identity often overshadows these moments. Dhillon’s attempt to combine genre elements and social critique is ambitious but ultimately detracts from the clarity and impact of the story. The film’s blend of high-stakes drama, moral ambiguity, and social messaging could have created an engaging experience. Still, the lack of cohesion in tone and direction makes it difficult for the audience to stay fully invested.

Despite these narrative shortcomings, Do Patti has its strengths. Sanon’s performance, particularly her ability to embody two characters with distinct identities, deserves credit. Although hampered by some forced dialogue, Kajol’s portrayal of Vidya is nevertheless a solid attempt at breaking from her usual roles. Ratassepp’s cinematography captures Uttarakhand’s landscapes in a way that reinforces the film’s atmosphere, even if the setting isn’t fully integrated into the narrative. For viewers who enjoy a blend of family drama with a dash of thriller, Do Patti provides an interesting, if uneven, watch.

In a cinematic landscape that often oversimplifies complex issues, Do Patti at least tries to raise awareness, even if it stumbles in execution. While it may deliver on only some fronts, its ambition is commendable. It offers an unconventional take on familiar tropes and attempts to delve into its characters’ psychological and social challenges. For casual viewers, Do Patti can serve as a visually and narratively engaging film, though those seeking a more nuanced portrayal of its themes may find themselves wanting more.

With its mix of captivating performances, scenic visuals, and ambitious storytelling, our Do Patti review is mostly positive. The film aspires to be both socially relevant and entertaining. But much like the mist-covered hills it’s set in, the narrative is occasionally obscured, leaving us with only glimpses of the powerful film it could have been.