Overhead, the thunderclaps continued roaring as the clouds coalesced for another storm. The past few days had seen enough of these storms—storms that had flooded most of eastern Bangladesh, marooned hundreds of thousands into homelessness, and killed several. Now another storm began to gather as Aritri held onto the edges of the wooden boat she was crossing the Gomati River on. The boat was traveling against the current. She braced against impact from the crushing waves of the turbulent floodwater, running rampant after the protective Gomati embankment failed to hold strong against the amassing rainwater and discharged dam water from across the border. This water now flooded parts of Comilla and the whole of Burichong—Aritri’s birthplace, the town where her father and mother were laid to rest, the graves now under threat by these violent tides.

The man operating the boat was a balding, tobacco-betel munching man who agreed to bring Aritri to Badarpur, which was now completely underwater. He was attired in a traditional lungi and a white shirt, with a gamcha wrapped around his head for protection from the expected rain. Aritri herself had brought her Shekhar umbrella. She had hired the man and his boat from Police Lines Road, where the last semblance of roadways was visible. Beyond that was a wasteland of murky water. About thirty minutes into the boat ride, they saw a stream of lost cattle—the confusion in their eyes overshadowed by their horror. The current of the water drifted them to the south, but the boat journeyed north upriver against the current. Around an hour into the journey, Aritri saw the first of many floating corpses. The bodies were unidentifiable. Their clothing was nondescript. Even the mangled and bloated shapes of the bodies made them seem androgynous. Nobody would ever be able to identify any of these bodies. Thankfully, she did not see any children floating.

The last time she was home, the country was run by a different government, and she was still a grad student vacationing from abroad. Last time, her parents’ remains were still underground in the large courtyard of their estate.

Last time she called home, those marked graves were still there, the estate was still there, and the lilies her cousin’s children excitedly told her about finally sprouting in the garden were also still there. Today, she was going home to desolation.

The rain had done this. Perhaps Allah was punishing them for the revolt. Perhaps it was something greater than Aritri could understand. But all the same, it was mainly the rain that had done this—made her countrymen suffer. But how could her faith waver when she herself had evidently reaped the benefit of the rain? Every time it poured, she would make a small prayer—which she did even today—and in any stretch of time, that wish would come to be. She was not a staunch believer, but she did believe, and she knew her wishes were the blessings of Allah. Then why had Allah done this to her home? To her countrymen?

When the floods began, she felt more helpless than she did during the near-seven-day internet blackout that took Bangladesh off the global map. At least she could call her friends and loved ones. During the floods, she could only watch the news helplessly. This helplessness compelled her to pack her bags and come help her countrymen. And when she learned her family home—which housed the graves of her parents—had flooded, she knew she had to save their remains. Or at least try.

The sky was darkening each minute, and the thunder only grew louder. Aritri knew the boatman was urging her to turn back with his nervous glances. She knew this was a hopeless mission. She would never be able to save those graves. The earth must have been removed by then. The remains washed away by the violent currents. The graves desecrated. And before long, the storm would break. But she only wanted a glance at her old house where she grew up alongside her cousins, the corridors of which were once scented by the wafting aroma of the garden flowers.

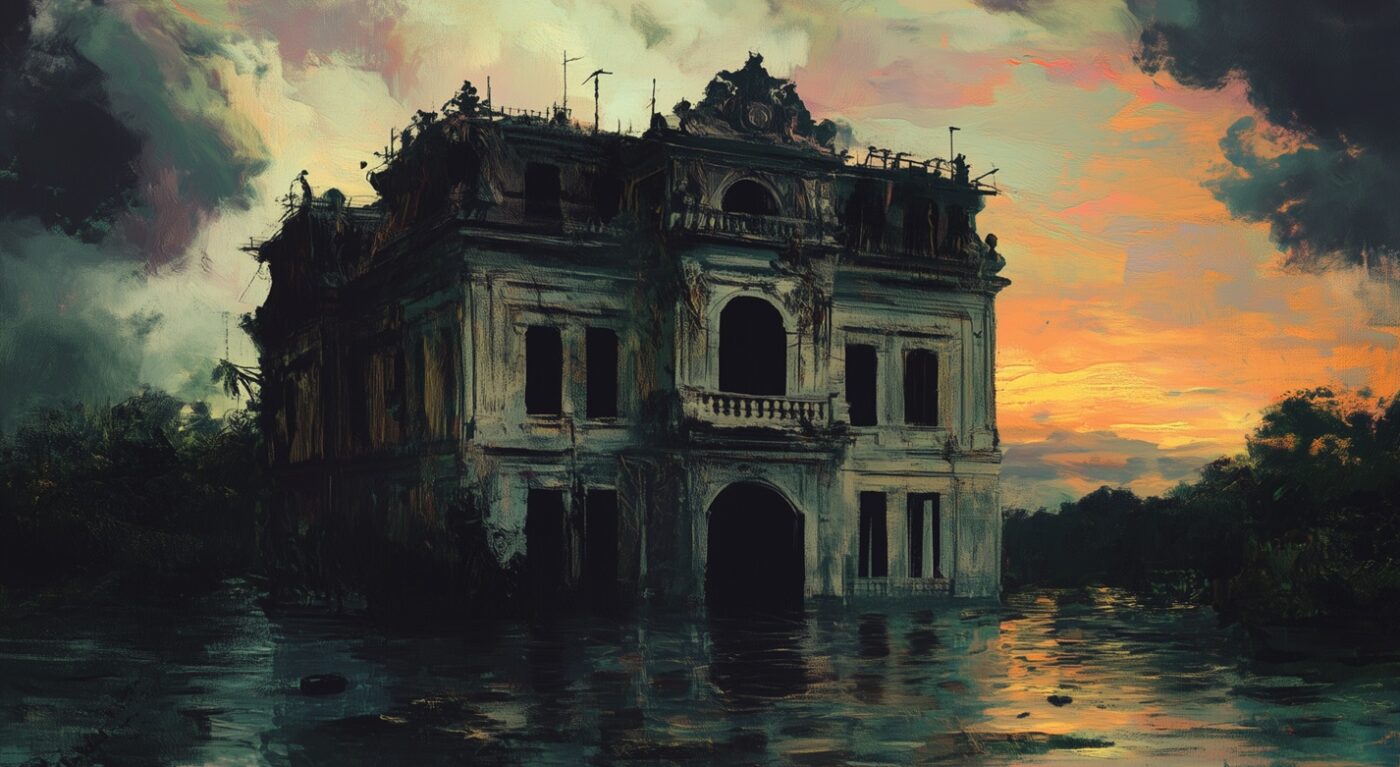

Toward the end of the second hour, Aritri finally saw the first sign of their estate up at Badarpur, still miles away. To her surprise, her heart filled with relief and happiness instead of sorrow. She was glad to see that familiar face one last time.

There were no other houses near it. The four-storied building, which once stood harrowingly tall thanks to the contrast in its empty surrounding, today stood short because of the floodwater—its head low, the lights long since turned off, no children screaming with excitement from the stairwells, no electricity passing in or out, no garden to speak of. However, Aritri was still glad to see it. She knew that was as far as they could go. She knew she would remember this moment for the rest of her life. Aritri wanted to stay a bit longer, look at the house a bit more, to make the memory a little more refined, a little more everlasting, but she knew it was time to turn back. She had already tried her luck by coming this far with the storm brewing overhead this intensely.

Aritri looked at the boatman to signal him her assent but found him looking up at the sky. She followed his gaze and saw the sun beginning to crack through the clouds. The dark-gray clouds were finally beginning to give in. Sometime unbeknownst to Aritri, the thunderclaps had ceased booming. She had not registered it until now. The waves calmed too. The boatman said, “সুবহানাল্লাহ!”

Aritri smiled in her heart. She stifled a choke and wiped tears from her face. She could come back with help later and salvage whatever she could from their estate. She could perhaps even protect the dignity of her parents’ graves. Her prayer had been answered. Allah had been watching her. There was hope yet for her and her countrymen.