I will be the first to admit that I haven’t had the closest connection to Bangla.

Growing up, I have consumed a lot more content in English than in Bangla, and being exposed to video games, movies and TV shows has a lot to do with that.

Funnily enough, most of my thoughts were in English too, until I shifted to Dhaka and enrolled in an English Medium school there. What’s ironic about that is that everyone there was used to conversing in Bangla, and it was a much more localized dialect than I was used to speaking.

Those were interesting years. The slangs came first, as you would expect from boys going through puberty.

Although we used to have programmes and small plays every year at our school on 21st February, the events didn’t personally resonate with me. I have always been more interested in world history, and for a while, I was more interested in the events of the American War of Independence or the French Revolution than I was in the Liberation War.

Studying Bangla during those years was something that seemed, while not entirely thankless, but not quite enjoyable. I was more into English Literature, and reading Greek (and Roman) myths, Shakespeare and King Arthur over the course of three years solidified that further.

There’s an idyllic, almost bucolic nature to Bangla that seemed unrelatable in the relentless hustle and bustle of Dhaka. Especially when you are stuck inside a car, rickshaw or the metal ribcage of a CNG, the cacophony of horns and pitched yells don’t make you terribly thrilled or in a contemplative mood.

It wasn’t until I started my undergrad and got familiar with the DU area near Shahbagh, and Dhanmondi nearby, that I formed more of a bond with Dhaka, and ultimately, Bengali. You could feel the roots of 20th century Dhaka in the Arts campus, and even more so in Curzon Hall, with its red-bricked buildings. From having jhalmuri near FBS or khichuri at Shadow, or sitting by the lake at Rabindra Shorobor.

I hadn’t been able to write as frequently during those first two years, but reconnected with it in my third and fourth years. When I was starting this blog in 2016, I often remember this urge to question myself, and others, about how Bangla made them feel, but I think I was asking the wrong people, or at least at the wrong time.

I remember exploring Bangla a couple of years later, through reading and writing, and finding some solace there.

It’s a strange experience, discovering your mother tongue on your own, how one must feel perhaps, when they grow up abroad and come to Bangladesh for the first time.

I could feel the outlines of the body of Bangla literature, and through a novice’s ears, develop a primitive understanding of Bangla music. And of course, there was the first time I watched Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne and was mesmerized by the magic of Satyajit Ray.

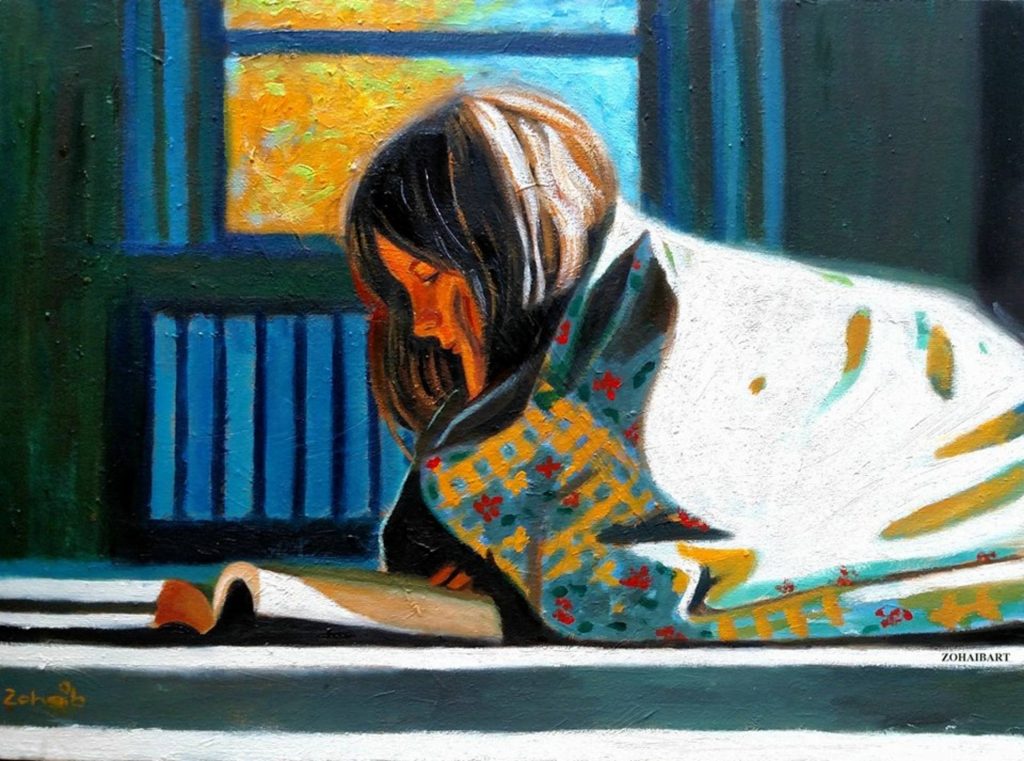

There are hundreds of beautiful Bangla words, and reading and writing them feels like running your fingers through beautifully embroidered kathas.

There is দিবানিশি, which means day and night; সাহিত্যানন্দ which means pleasures of literature; অরুন্ধতী, which is a star; তেজস্বিনী, which means high spirited woman, and many more.

I wish I could write well enough in Bangla to feel confident enough to share my musings publicly, but that will take a while. At the moment, I feel more in tune with my origins, and can appreciate the sacred values of a language that people died to preserve.

Around 40% of people worldwide do not have the option of learning their mother tongue in schools. We are quite blessed to have inherited such a proud heritage in this regards.

If I were to think of languages as musical instruments, then Bangla seems to be something akin to a flute, while English is more akin to a keyboard or a piano, and something more aggressive like German similar to drums or other percussion-oriented instruments.

When I anthropomorphize Bangla, I see a band of traveling musicians traveling by the river, singing Baul songs with the flute and aktara. It’s a vision of a past that almost seems nonexistent, but it’s one of the images of our collective cultural identity that holds us together.