Netflix’s Maniac, based on a Norwegian series of the same name and directed by Cary Fukunaga (True Detective Season One), stars Emma Stone and Jonah Hill.

It’s ten episodes of trippy, soulful exploration of minds, simulations and multiple worlds, weaved around a story of healing and overcoming grief and alienation.

The story takes place in a quasi-futuristic version of New York City, where bots and AIs are commonplace but people still use pre-Mac PCs. Instead of Facebook Ads, you have Ad Buddy, where a person literally reads ads to you and pays you for listening to them. You also have Friend Proxy, a service where you can hire fake friends. This isn’t too dissimilar to our world, where we can use apps like RABF to rent boyfriends.

Dealing with Grief and Isolation

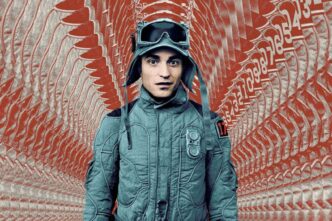

Owen (Jonah Hill) and Annie (Emma Stone) meet each other when applying for a paid medical trial at Neberdine Pharmaceuticals. Owen is recovering from familial trauma and, after being visited by an apparition of an imaginary brother, seeks Annie out for a mission of higher purpose.

The pair journey through a psychedelic and often grim program where they must deal with their mental conditions through three phases: identification, exploration and confrontation. Things would have been hard enough for Owen and Annie, but the AI overseeing their trials is also going through profound depression.

Maniac is best watched through in one sitting. It’s designed by Netflix for binge-watching.

It jumps from one scenario to the next: from an eighties couple trying to save a lemur to a pair of on-again-off-again lovers trying to still a priceless manuscript during a seance. There are fantasy scenarios, and then there’s a bizarre sixties episode featuring the death of a minute alien.

Less than the Sum of its Parts

However, if you think about it, it starts to fall apart. It’s a clear case of a flashy marriage between algorithmic analysis and big moment film-making.

The overall vision of Maniac is nebulous.

It tackles a potent subject, but while it uses Justin Theroux’s Dr. Mantleray to great effect, it brings to mind another great series with the actor that also tackled human emotion and loss: The Leftovers. That’s especially telling, since the showrunner, Patrick Somerville, also worked as a writer on the HBO show.

There’s some meat in Mantleray’s conflict with his mother, and how that affected GRTE, the computer. However, the show mainly focuses on hyperactive, heavy-handed declarations rather than sincere explorations of grief. There is some earnestness in Annie’s grief over her sister’s loss, and in the sheer isolation felt by Owen. The ending does well by the two characters, showing how the two support each other as friends instead of going the usual romantic route.

Stone does better with the different personas than Hill. She effortlessly shifts from being a Jersey housewife, to a femme fatale and then a warrior elf. Hill is much more muted and glum. He does shine, however, in the role of Snorri, a disgraced Icelandic spy who chortles in rapturous glee at the sight of Stone gunning down countless men.

Good Algorithms Don’t Always Make for Great Television

As good as Maniac is, however, it isn’t great. And that makes me feel uneasy, especially given how well-crafted it is, not only in terms of production values and cinematography, but also in terms of data analysis. “Because Netflix is a data company, they know exactly how their viewers watch things,” explained Cary Fukunaga in a GQ profile. “So they can look at something you’re writing and say, we know based on our data that if you do this, we will lose this many viewers. So it’s a different kind of note-giving. It’s not like, Let’s discuss this and maybe I’m gonna win. The algorithm’s argument is gonna win at the end of the day.”

Somerville and Fukunaga’s collaboration was novel, and they figured out early on how to split their duties effectively. “While I do think visually, I focus much more on character stuff along the way,” said Somerville. “I lean a little bit towards more episodic storytelling, that older model of television — the episode being the thing. I think Cary leans a little bit more toward thinking about this as one story, this long form. I think that was a good tension for us.”

At the end of the day, Maniac isn’t dreamy, weird or earnest enough to really achieve what it wants to. But it makes good progress in getting there. Somerville’s writing is taut, Fukunaga’s directing is superb, and the acting on display is great. It’s good TV, as long as you consume it in one sitting and then quickly move onto the next snack.