Remember the girl who’s smart and perfectly imperfect; she’s beautiful but broken, and stays in her own little world? She’s everything you want but cannot have.

How familiar is a female character who plays all the games you play, likes everything you like, and has some ‘radical’ hairstyle? She has a “perfect body” but hides it under baggy clothes, and wears video game centric t-shirts. She is the most beautiful woman in the universe, but nobody saw her exist, until you noticed her.

You see how above described characters are based entirely around a guy’s shallow definition of a “perfect girl”. The concept of female mains and sides in media has become equivalent to that of a pre-packaged girlfriend. We call this a manic pixie dream girl. It’s often a frustrated author who writes himself a perfect girlfriend. When she inevitably proves more difficult to handle in the relationship than she did in his fantasy, she quickly “fixes” herself to be lovable and a keeper (like the makeover of Sanjana for Lucky in Main Hoon Na).

What is a Manic Pixie Dream Girl?

A Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) is a stock character in films that refers to “that bubbly, shallow, cinematic creature that exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” In simple terms- a female romantic lead who is nothing more than her pretty face, outgoing personality, and whacky attitude, whose sole purpose is to help male protagonists- typically dealing with complex psychosocial issues- to lighten up and enjoy their lives. MPDGs are one-dimensional characters who have eccentric personality quirks and only seek the happiness of the male protagonist, deal with no complex issue, and invariably serve as the romantic interest.

Did you love these MPDG characters?

Scarlett Johansson in Her and A Marriage Story is all you need to understand the difference in projecting female characters.

Throughout Hollywood history, male-dominated perspectives often left us with underdeveloped female characters that offered nothing more than the idea that women are there to add colours to a man’s otherwise dull life and help him appreciate the universe’s wonders. Claire Colburn, played by Kristen Dunst in Elizabethtown, was the first character to be called a MPDG. But the first depiction was probably in Bringing up Baby with Katharine Hepburn. Other significant MPDG characters were Zooey Deschanel in 500 Days of Summer, Emma Stone in La La Land, Emma Watson in The Perks of Being a Wall Flower, etc. While we all love and adore her, Audrey Hepburn was quintessentially the epitome of MPDG trope.

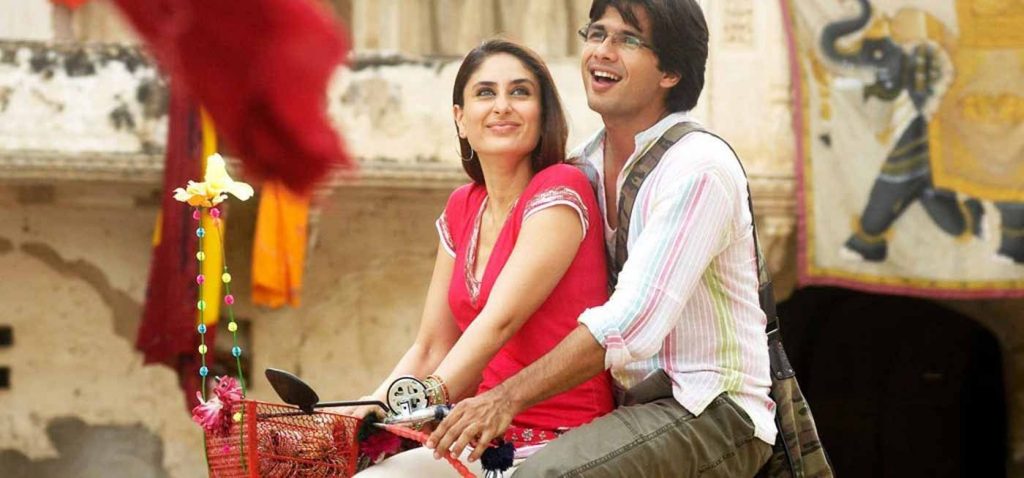

While in Hollywood, a classic MPDG is ecstatic, with crazy hair colours and a sneaky sex appeal, in south-Asian narrative, she is super kempt, obedient, pale skinned and always sexually coy; she has a voice, but never louder than the hero’s and fantasizes to be a martyr protecting the family unity. Dimple Kapadia as even the title character in Bobby to Shraddha Kapoor in Ek Villain were so sunny that you’d get blinded by their hearts of glitter, Kareena Kapoor since the 90s with Poo in K3G to Geet from Jab We Met– the queen of MPDG, Katrina Kaif in ZNMD, Nargis Fakhri in Rockstar, Deepika Padukone in Tamasha, the list is endless yet the audience never sees their personality flaws, insecurities and moments of vulnerability where their mascara is not on point.

What are the Consequences of MPDG?

Men grow up expecting to be the hero of their own story. Women learn the only way to play the supporting actress in someone else’s story is by centering their life catering to men’s emotional needs and growth. Stories matter. Stories are how we make sense of the world; and the colossal narrative injustice done to female characters in all media alike reeks of inherent sexism and is downright derogatory and misogynistic. When you’re a young girl, you expect to grow up into forgettable supporting characters, or if lucky, slung over the hero’s shoulder and married off in the last page. The only way you get to be in stories is to be stories yourself. You are what happens to the hero.

Yet in real life, men do love women whose lives don’t revolve around catalyzing male transformation. The MPDG ideal exists because too many boys remain intimidated by women who exist independently. We need to stop glorifying female contribution in man’s life. We need to stop measuring their value solely against their martyrdom in romance and start seeing women as having minds of their own.

Can we fix MPDG characters?

Character development can add to their personality and interests over time. The story may be told from their perspective. An MPDG with an independent story arc and character depth can be the true main character of a work, with his auxiliary role assisting her goals. An alternative type of deconstruction is for an MPDG to switch from cute-and-psycho to realistically, a damaged and unhealthy individual whose childishness, naivete, and compulsive behavior causes chaos in her daily life.

We seek persons, not girls. It is definitely easier to be a girl than it is to do the work of being a grown woman, dealing with her own problems, having her bad days and sometimes spilling its effect on her counterpart too because above all, she’s humane. Women do not handle the impacts of their psychosocial issues such that no inconvenience is caused to their love interest, if any. All those lazy stereotypes and hurtful put-downs are definitely a joke, until they aren’t, and we clearly need to take the sexism and power dynamics seriously.

The one secret I reveal to you through this article is that we’re not fantasies, and we weren’t made to save anyone, nor should we have to; we’re real people, with faults and flawed personalities and big dreams.

Tell stories of women who do their own magic because they aren’t fairy tales, and of men who love them for the complicated, messy, decidedly non-ethereal people they are.