There’s a chance you have heard that quote about the definition of insanity, especially if you played a video game called FarCry 3.

“Do you know what the definition of insanity is?” Vaas asked, talking to the protagonist, and thus the players themselves. “It’s doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

The first draft of this article stretches back to last August. This is the first time I am revisiting a draft that’s older than three weeks. And although more than eight months have passed since I completed that first draft, I find myself faced with the same contextual ethos as before.

When talking about road safety, there’s always that small kernel of fear that seems to have become lodged in your head. The fear that, maybe tomorrow, the person who gets run over will be someone you cherish. And maybe, the day after that, you will be the person whose head gets squashed like a watermelon by a bus tyre.

Whatever the case may be, the disturbingly familiar scenario of students protesting after a gruesome hit and run has garnered a wide range of polarising opinions. While the rest of us are still vacillating, over the purpose of these protests, one group has gone forward boldly into areas that few others dare to tread.

I am talking about the fearless artists who continue to embody the cultural zeitgest of Bangladeshi youths succinctly through their artworks. They know, as do we, that there is a power to be found among provocative words and visuals. Wordsmiths know this, as do artists, and creators of any kind.

Innovation and creativity often requires critical thinking. Thus artists often tend to be excellent at making observations, because they come to adapt a questioning mindset that cuts through the miasma of our day-to-day lives.

Last August, I talked to a few artists who were expressing their support of the protests through their work. “The protest is the most beautiful thing I have seen in years,” said Mahatab Rashid, a cartoonist who contributes to the popular comedy supplement, Rosh+Alo. “It’s mesmerizing, brilliant, and otherworldly. It’s like a magic realism novel, in the vein of Gabriel Garcia Márquez.”

Mahatab also maintains his own page, Mahakabbo, which has its own dedicated followerbase. I connected with Mahatab instantly when he talked about magical realism. I discussed with Mahatab my own experience with the trope, which I first experienced in Season One of Netflix’s Narcos.

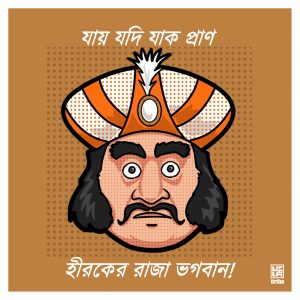

“I draw what I see and feel, and I draw what I think I should,” said Tirtho, another cartoonist whose artwork has resonated with the social media denizens during these extraordinary times. “I personally feel the responsibility to speak against the day-to-day injustices we face as ordinary citizens, while society and state turn a blind eye. I am always prepared to say the harsh truth. Whether it hurts or pleases anyone, I don’t really care.

I support the protesters wholeheartedly. I hope it shakes the rotten system to the core and help builds a new one.”

Mahatab, although less of a gritty firebrand, voiced similar sentiments. “Although this isn’t my first viral artwork, I am overjoyed by the tremendous love and support I am getting from everyone. It’s almost become a symbol for this movement. Nothing makes me prouder than that.”

Other than Mahatab Rashid and Tirtho, several cartoonists with robust followings, such as Oishik Jawad, Shah Shariyar and Arts by Rats have produced viral artworks as well. However, it would be unfair not to give proper due to the dozens, if not hundreds of creators who are expressing solidarity through their works as well.

Art is a power. This power needs to be exercised, so that we can etch memorable, provocative images, words and tunes into our brains. This potent transformative power of art and literature has been harnessed throughout human history to great effect.

Les Misérables, for instance, has immortalized the 1832 June Rebellion in Paris, which would have been forgotten in a few years if Victor Hugo left the matter untouched. The powerful characterization of Javert and Jean Valjean also makes Hugo’s story all the more poignant and powerful. The story ends seventeen years after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. The sheer idealism of Marius and his compatriots is crushed when faced with reality, yet the story lionizes and applauds the youth for their misguided efforts.

I do not know who the Valjeans and Javerts are in Dhaka right now, but for now, the Victor Hugos are doing more than their fare share of work to create memories. These memories serve as narrative landmarks, and as long as they remain etched in our minds, no one can take them away from us.